DRAGON

Short StoriesThe Black House

Eleven

Little Tales of Misogyny

Short Stories

The Black House

Eleven

Little Tales of Misogyny

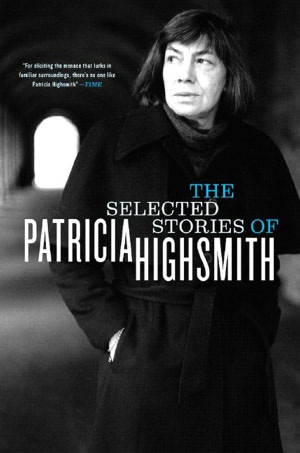

Patricia Highsmith

(1921 - 1995)

Biography of Patricia Highsmith

Patricia Highsmith was born in Fort Worth, Texas, on 19.01.1921 and died on 04.02.1995 in Locarno (Ticino). She was raised in Fort Worth, Texas, and in New York where she studied and found work as a text writer for comic strips. Following the publication of her first thriller, Strangers on a Train (1950), she was able to make a living as a writer. She traveled extensively, especially to and in Europe, taking up residence in England in 1963. She moved to France in 1967 and finally to Switzerland (Ticino) in 1981. Patricia Highsmith wrote more than 20 novels, plus many short stories, essays and articles for the media. She owed much of her fame to the five Ripley novels, featuring the murderer and anti-hero Tom Ripley, who always somehow managed to cover up his tracks. Only part of her work is crime fiction however. Highsmith was above all concerned with the psychology of her characters, and with human relationships and the way in which they degenerate into violence. The novel The Price of Salt deals with the subject of a Lesbian relationship. Her works have inspired several films, by such well known directors as Alfred Hitchcock, Claude Chabrol, Wim Wenders and Anthony Minghella.

|

| Patricia Highsmith aged twenty-one. |

PATRICIA HIGHSMITH

(1921 -1995)

BIOGRAPHY

Mary Patricia (née Plangman, stepfather's name Highsmith); has also written as Claire Morgan. American mystery writer, whose works were especially successful in Europe. Highsmith has explored the psychology of guilt and abnormal behavior in a world without firm moral ground. Often her novels deal with questions of fading identity and double personality. She also published several volumes of short stories in the fields of fantasy, horror, and comedy. Alfred Hitchcock'sStrangers on a Train was based on Highsmith's novel. Her series character, Tom Ripley, has inspired several films.

"But the beauty of the suspense genre is that a writer can write profound thoughts and have some sections without physical action if he wishes to, because the framework is an essentially lively story. Crime and Punishment is a splendid example of this. In fact, I think most of Dostoyevsky's books would be called suspense books, were they being published today for the first time. But he would be asked to cut, because of production costs." (from Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, 1966)

Patricia Highsmith was born in Fort Worth, Texas, but she grew up in New York. Her parents, who separated before she was born, were both commercial artists. Her father was of German descent and she did not meet him until she was twelve – the surname Highsmith was from her stepfather. For much of her early life, she was cared for by her maternal grandmother. Her great-grandmother Willi Mae was "a Scot, very practical, though with a great sense of humor, and very lenient with me," Highsmith later recalled.

Highsmith was educated at Julia Richmond Highschool in New York and at Columbia, where she studied English, Latin and Greek, earning her B.A. in 1942. According to some sources, Highsmith spent some time providing story-lines for the comics after leaving college. It is believed she worked on scripts for Black Terror and possibly Captain America.

Highsmith showed artistic talent from an early age – she painted and remained talented sculptor, but she had determined to be a writer. She had written as a teenager stories and edited the school magazine at Barnard College, and after leaving college she worked with comic books, supplying the writers with plots. Before her first book, Highsmith had a number of jobs, including that of a saleswoman at a New York Store.

As a writer Highsmith made her debut with STRANGERS ON A TRAIN (1950). It depicts two men, an architect and a psychopath, who meet on a train, and "swap" murders. "Any kind of person can murder. Purely circumstances and not a thing to do with temperament! People get so far – and it takes just the least little thing to push them over the brink. Anybody. Even your grandmother. I know." (from Strangers on a Train) Highsmith developed the idea further in THE BLUNDERER (1954), where a man's wife dies accidentally but people become suspicious when he regularly visits another who had murdered his wife. "Some people are better off dead -like your wife and my father, for instance," states Bruno, the rich psychopath and proceeds to carry out his part of the bargain. This work set the tone for her following novels, in which two different worlds intersect and the border between normal and abnormal persons is seen vague and perhaps nonexistent.

The cunningly plotted melodrama inspired the director Alfred Hitchcock who made it into film. Both the book and the film are considered classic in the suspense field. The story has also been filmed later, in 1969 under the title Once You Kiss a Stranger, directed by Robert Starr. It did not gain much attention, but Danny DeVito' spinn-off Throw Momma From the Train (1987), which turned the story into black comedy, was better received.

Highsmith's THE PRICE OF SALT (1953) appeared under the pseudonym Claire Morgan after her publishers had turned it down. The homosexual love story between a married woman and a shopgirl was in its time unusual and sold almost million copies. In 1991, the book was reissued with an afterword under the title CAROL. Highsmith dealt with sexual minorities in her other works, and her final novel, SMALL G: A SUMMER IDYLL (1995), depicted a bar in Zurich, where a number of homosexual, heterosexual, and bisexual characters are in love with the wrong people. Highsmith herself had a number of lesbian affairs, but in 1949 she also become close to the novelist Marc Brandel. Between 1959 and 1961, Highsmith had a relationship with Marijane Meaker, who wrote under the pseudonym M.E. Kerr.

Tom Ripley, Highsmith's most popular character, is a small-time con man and bisexual serial killer, who was introduced to the world in THE TALENTED MR. RIPLEY (1955). The critic and awarded mystery writer H.R.F. Keating included the work in hisCrime & Mystery: the 100 Best Books (1987). In its foreword Highsmith wrote: "I now have a different view of Cornell Woolrich, thanks to the two pages on him here. Keating describes The Bride Wore Black, and Woolrich's curious and indirect methods of laying out his plot and his clues. A homosexual who apparently lived in the closet, Woolrich shared a life in residential hotels with a mother whom he both loved and hated. Could anything be worse?" At the beginning of the story, Ripley is a small-time grifter in New York, and in the end he is a double murderer. Ripley meets a worried rich father, whose stay-away son, Richard, lives in Europe. He is willing to finance Tom's trip to Europe to contact him. In Italy, he ends up killing his rich friend in a boat at San Remo, and assumes his identity. Then he kills one of Richard's friends. Without conscience, Ripley is incapable of remorse. He survives against all odds, like a strange, new kind of creature. The book was first filmed in 1960 under the title Plein Soleil (Purple Noon), directed by René Clément, starring Alain Delon. The likeable amateur murderer Ripley inspired the Wim Wenders film The American Friend (1977), starring Dennis Hopper, Bruno Ganz, Samuel Fuller, and Nicholas Ray. In the story Ripley becomes involved with the Mafia and he uses a non-professional hit-man, whose fate is sealed.

In Anthony Minghella's film from 1999 Highsmith's homosexual subtext is not hidden. In the story a millionaire asks Ripley to track down his son, Dickie, who is living in Italy. The prodigal son and Ripley became friends, but when Dickie wants to get rid of his new associate, Ripley starts to lie and kill to continue the high life he has found so attractive. Dickie vanishes, and Ripley appropriates his identity for fun, to keep up his lifestyle and to fill the emptiness of his weak character.

Ripley became Highsmith's most enduring character, who could be a sadist and an understanding husband, a parody of upper-class mentality and a criminal only by force of circumstances. "Murder, in Patricia Highsmith's hands, is made to occur almost as casually as the bumping of a fender or a bout of food poisoning," wrote Roberts Towers in The New York Review of Books. The thrill of the novels is based on the problem, how Ripley is going to get away again with his crime. Like Dorian Gray, he lives a double life, but remains unpunished for his actions. After The Talented Mr. Ripley the ambivalent hero appeared in several sequels, among them RIPLEY UNDER GROUND (1970), in which he both masquerades as a dead painter and kills an art collector, RIPLEY'S GAME (1974), a story of revenge, in which Ripley is paired with a first-time murderer, THE BOY WHO FOLLOWED RIPLEY (1980), and RIPLEY UNDER WATER (1991), the final Ripley adventure, in which Ripley is pursued by a sadistic American, who knows too much of his past. This time Ripley doesn't kill anybody. "The feeling of menace behind most Highsmith novels, the sense that ideas and attitudes alien to the reasonable everyday ordering of society are being suggested, has made many readers uneasy. One closes most of her books -- and her equally powerful and chilling short stories -- with a feeling that the world is more dangerous than one had imagined." (Julian Symons in The New York Times, October 18, 1992)

As a reclusive person, Highsmith spent most of her life alone. "People forget that she was a very conservative person," said the American playwright Phyllis Nagy, "she wasn't bohemian like Jane Bowles and she did hold some very weird and contradictory views." The publisher Otto Penzler, who admired her work and brought her in the mid-1980s to New York, described her as the most unloving and unlovable person he have ever known.

In 1957, Highsmith won the French Grand Prix de Litterature Policiere and the British Crime Writers Association awarded her in 1964 a Silver Dagger. In 1979, she received the Grand Master award by the Swedish Academy of Detection. Although writing remained her true passion, she also showed talent as an artist and sculptress. Highsmith moved permanently to Europe in 1963, living in East Anglian and France. Her final years Highsmith spent in an isolated house near Locarno on the Swiss-Italian border. She never abandoned her Texan background, dressing in 34-inch-waist Levis, sneakers and neckerchiefs. Highsmith died in Switzerland on February 4, 1995.

Highsmith's works outside mystery genre include a juvenile book, short stories, and non-fiction. In PLOTTING AND WRITING SUSPENSE FICTION (1966) she stated that "art has nothing to do with morality, convention or moralizing." Several of Highsmith's works fall out from the mystery genre and her crime novels often have more to do with psychology than conventional plotting. "Her peculiar brand of horror comes less from the inevitability of disaster, than from the ease with which it might have been avoided. The evil of her agents is answered by the impotence of her patients - this is not the attraction of opposites, but in some subtle way the call of like to like. When they finally clash in the climactic catastrophe, the reader's sense of satisfaction may derive from sources as dark as those which motivate Patricia Highsmith's destroyers and their fascinated victims." (Francis Wyndham inLesbian and Bisexual Fiction Writers, ed. by Harold Bloom, 1997) Russel Harrison has argued that Highsmith's fiction demonstrates elements of existentialism as linked to Sartre and Camus, and reflects sociopolitical concerns to the gay and lesbian issues of 1980s and 1990s. Graham Greene has remarked that the world of a Patricia Highsmith novel is "claustrophobic and irrational which we enter each time with a sense of personal danger".

For further reading: Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith by Andrew Wilson (2003); Murder Most Fair: The Appeal of Mystery Fiction by Michael Cohen (2000); Mystery and Suspense Writers, vol. 1, ed. by Robin W. Winks (1998); Lesbian and Bisexual Fiction Writers, ed. by Harold Bloom (1997); Patricia Highsmith by Russell Harrison (1997); Über Patricia Highsmith, ed. by Franz Cavigelli and Fritz Senn (1980). "Miss Highsmith is a crime novelist whose books one can reread many times. There are wery few of whom one can say that. She is a writer who has created a world of her own - a world claustrophobic and irrational which we enter each time with a sense of personal danger..." (Graham Greene, 'Introduction' to THE SNAIL-WATCHER, 1970). Lisätietoja:ks. mm. teoksesta Murha ei tunne rajoja, Book Studio (1997) Jorma-Veikko Sappisen artikkeli 'Salaperäisen naisen lumoissa'.

Selected works

- STRANGERS ON A TRAIN, 1950 - Muukalaisia junassa (suom. Annika Eräpuro, 1990) - Films: 1951, dir. by Alfred Hithcock, screenplay by Raymond Chandler and Czenzi Ormonde, starring Farley Granger as Guy Haines), Robert Walker (as Bruno Antony), Ruth Roman (as Anne Morton), Leo G. Carroll. "Mr Hitchcock again is tossing a crazy murder story in the air and trying to con us into thinking that it will stand up without support... His basic premise of fear fired by menace is so thin and so utterly unconvincing that the story just does not stand... Farley Granger plays the terrified catspaw (as he did in Rope) as though he were constantly swallowing his tongue." (Bosley Crowther in The New York Times, July 4, 1951); uncredited: Once You Kiss A Stranger, 1970, prod. Warner Brothers/Seven Arts, dir. by Robert Sparr, screenplay Norman Katkov, Frank Tarloff, starring Paul Burke, Carol Lynley, Martha Hyer, Peter Lind Hayes; TV film: Once You Meet a Stranger, 1996, dir. Tommy Lee Wallace, starring Jacqueline Bisset, Art Bonilla and Kathryne Dora Brown.

- THE PRICE OF SALT, 1952 (as Claire Morgan, published in 1991 under the title Carol)

- THE BLUNDERER, 1954 (as Lament for a Lover, 1956) - Film: Le meurtrier, 1954, prod. Cocinor, Corona Filmproduktion, Galatea Film, dir. by Claude Autant-Lara, starring Maurice Ronet, Marina Vlady and Robert Hossein.

- THE TALENTED MR. RIPLEY, 1955 - Lahjakas herra Ripley (suom. Jorma-Veikko Sappinen, 1984) - TV film 1956, prod.Columbia Broadcasting System, dir. Franklin J. Schaffner, written by Marc Brandell, Patricia Highsmith, starring Keefe Brasselle, Betty Furness and William Redfield; Plein soleil, 1960, dir. by René Clément, starring Alain Delon as (Tom Ripley), Maurice Ronet and Marie Laforêt; 1999, prod. Miramax International, Paramount Pictures, Mirage Enterprises, dir. by Anthony Minghella, starring Matt Damon (as Tom Ripley), Philippe Greenleaf, Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow. "Our reviewer feels something of the sordiness and nasty undertones may have been lost in the rendering, even if the new film version boasts many laudable qualities from the exquisite score, montage and production values to beautiful photography and competent casting. Another change, the obvious homosexuality of the protagonist, proves likewise problematic, since the author tended to keep her readers on a more speculative leash, especially with the later books in the canon." (from Ruumiin kulttuuri, 1/2000)

- DEEP WATER, 1957 Film: Eaux profondes, 1981, dir. Michel Deville, starring Isabelle Huppert, Jean-Louis Trintignant and Sandrine Kljajic; TV film: Tiefe Wasser, 1983, dir.Franz Peter Wirth starring Sven Eric Bechtolf, Peter Bongartz, Franziska Bronnen, Sky Dumont.

- MIRANDA THE PANDA IS ON THE VERANDA, 1958 (with Doris Sanders)

- A GAME FOR LIVING, 1958

- THIS SWEET SICKNESS, 1960 Film: Dites-lui que je l'aime, 1977, prod. Filmoblic, France Regions 3 (FR3), Prospectacle, dir. Claude Miller, adaptation by Claude Miller, Luc Béraud, starring Gérard Depardieu, Miou-Miou, Claude Piéplu, Jacques Denis.

- THE CRY OF THE OWL, 1962 - TV movie: Der Schrei der Eule, 1987, prod. TV-60 Filmproduktion (West Germany), dir. Tom Toelle, with Matthias Habich, Birgit Doll, Jacques Breuer; Le cri du hibou, 1987, dir. Claude Chabrol, prod. Civite Casa Films, Italfrance Films, TF1, starring Christophe Malavoy, Mathilda May, Jacques Penot; The Cry of the Owl, 2009, dir. Jamie Thraves, starring Paddy Considine, Julia Stiles and Karl Pruner.

- THE TWO FACES OF JANUARY, 1964 - Film: Die zwei Gesichter des Januar, 1986, prod. Monaco Film GmbH (West Germany), dir. Wolfgang Storch, Gabriela Zerhau, starring Charles Brauer, Yolande Gilot, Thomas Schücke.

- THE GLASS CELL, 1965 Film: Die gläserne Zelle, 1978, prod. Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR), Radiotelevisão Portuguesa (RTP), Roxy Film, dir. Hans W. Geissendörferstarring Brigitte Fossey, Helmut Griem, Dieter Laser.

- THE STORY-TELLER, 1965 (UK title: A Suspension of Mercy) - Viimeiseen hetkeen (suom. Jorma-Veikko Sappinen, 1993)

- PLOTTING AND WRITING SUSPENSE FICTION, 1966

- THOSE WHO WALK AWAY, 1967

- THE TREMOR OF FORGERY, 1969 - Film: Trip nach Tunis, 1993, prod. Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR), Kick Film, Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (MDR), dir. Peter Goedel, starring David Hunt, Karen Sillas, John Seitz, Ulrich Günther.

- RIPLEY UNDER GROUND, 1970 Film 2004, prod. Cinerenta Medienbeteiligungs KG, dir. by Roger Spottiswoode, screenplay by Blake Herron and Donald E. Westlake, starring Barry Pepper (as Tom Ripley), Tom Wilkinson, Jacinda Barrett, Willem Dafoe.

- THE SNAIL-WATCHER AND OTHER STORIES, 1970 ( foreword by Graham Greene)

- A DOG'S RANSOM, 1972 - Lunnaat -TV film: La rançon du chien, 1996 , dir. Peter Kassovitz, starring François Négret, Daniel Prévost and François Perrot.

- RIPLEY'S GAME, 1974 - Film 1977, dir. by Wim Wenders, starring Dennis Hopper (as Tom Ripley), Bruno Ganz, Samuel Fuller, Nicholas Ray; Ripley's Game, 2002, prod. Cattleya, Baby Films, Mr. Mudd, dir. by Liliana Cavani, starring John Malkovich (as Tom Ripley), Dougray Scott, Lena Headey, Chiara Caselli

- KLEINE GESCHICHTEN FÜR WEIBERFEINDE, 1974 - (UK title: Little Tales of Misogyny, 1977) - TV movie: Petits contes misògins, 1995, prod. Televisió de Catalunya (TV3) / Spain, dir. Pere Sagristà, starring Mamen Duch, Míriam Iscla, Marta Pérez.

- THE ANIMAL-LOVER'S BOOK OF BEASTLY MURDER, 1975

- EDITH'S DIARY, 1977 - Film: Ediths Tagebuch, 1983, dir. Hans W. Geissendörfer, starring Angela Winkler, Vadim Glowna, Leopold von Verschuer, Hans Madin.

- SLOWLY, SLOWLY IN THE WIND, 1979

- THE BOY WHO FOLLOWED RIPLEY, 1980 - Ripley ja poika (suom. Jorma-Veikko Sappinen, 1995)

- THE BLACK HOUSE, 1981

- THE PEOPLE WHO KNOCK ON THE DOOR, 1983

- MERMAIDS ON THE GOLF COURSE, 1985

- FOUND IN THE STREET, 1986

- TALES OF NATURAL AND UNNATURAL CATASTROPHES, 1987

- CHILLERS, 1990

- RIPLEY UNDER WATER, 1991 -

- A SMALL G: A SUMMER IDYLL, 1995

- THE SELECTED STORIES OF PATRICIA HIGHSMITH, 2001

- NOTHING THAT MEETS THE EYE: THE UNCOLLECTED STORIES OF PATRICIA HIGHSMITH, 2002

- THE COMPLETE RIPLEY NOVELS, 2009

http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/highsm.htm

“I won't ever set the world on fire as a painter,' Dickie said, 'but I get a great deal of pleasure out of it.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley

Highsmith’s book Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction is an inspiring primer for budding psycho-crime novelists

Sam Jordison

Tuesday 16 June 2015 17.19 BST

QUOTES

By Patricia Highsmith

“But there was not a moment when she did not see Carol in her mind, and all she saw, she seemed to see through Carol. That evening, the dark flat streets of New York, the tomorrow of work, the milk bottle dropped and broken in her sink, became unimportant. She flung herself on her bed and drew a line with a pencil on a piece of paper. And another line, carefully, and another. A world was born around her, like a bright forest with a million shimmering leaves.”

― Patricia Highsmith, Carol

― Patricia Highsmith, Carol

“It would be Carol, in a thousand cities, a thousand houses, in foreign lands where they would go together, in heaven and in hell.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“Then Carol slipped her arm under her neck, and all the length of their bodies touched fitting as if something had prearranged it. Happiness was like a green vine spreading through her, stretching fine tendrils, bearing flowers through her flesh. She had a vision of a pale white flower, shimmering as if seen in darkness, or through water. Why did people talk of heaven, she wondered”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“What was it to love someone, what was love exactly, and why did it end or not end? Those were the real questions, and who could answer them?”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“Do people always fall in love with things they can't have?'

'Always,' Carol said, smiling, too.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

'Always,' Carol said, smiling, too.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“How was it possible to be afraid and in love... The two things did not go together. How was it possible to be afraid, when the two of them grew stronger together every day? And every night. Every night was different, and every morning. Together they possessed a miracle.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“Their eyes met at the same instant moment, Therese glancing up from a box she was opening, and the woman just turning her head so she looked directly at Therese. She was tall and fair, her long figure graceful in the loose fur coat that she held open with a hand on her waist, her eyes were grey, colorless, yet dominant as light or fire, and, caught by them, Therese could not look away. She heard the customer in front of her repeat a question, and Therese stood there, mute. The woman was looking at Therese, too, with a preoccupied expression, as if half her mind were on whatever is was she meant to buy here, and though there were a number of salesgirls between them, There felt sure the woman would come to her, Then, Then Therese saw her walk slowly towards the counter, heard her heart stumble to catch up with the moment it had let pass, and felt her face grow hot as the woman came nearer and nearer.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“Do you like her'

''Of course!' What a question! Like asking her if she believe in God.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“Carol raised her hand slowly and brushed her hair back, once on either side, and Therese smiled because the gesture was Carol, and it was Carol she loved and would always love. Oh, in a different way now because she was a different person, and it was like meeting Carol all over again, but it was still Carol and no one else. It would be Carol, in a thousand cities, a thousand houses, in foreign lands where they would go together, in heaven and in hell. Therese waited. Then as she was about to go to her, Carol saw her, seemed to stare at her incredulously a moment while Therese watched the slow smile growing, before her arm lifted suddenly, her hand waved a quick, eager greeting that Therese had never seen before. Therese walked toward her.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

''Of course!' What a question! Like asking her if she believe in God.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“Carol raised her hand slowly and brushed her hair back, once on either side, and Therese smiled because the gesture was Carol, and it was Carol she loved and would always love. Oh, in a different way now because she was a different person, and it was like meeting Carol all over again, but it was still Carol and no one else. It would be Carol, in a thousand cities, a thousand houses, in foreign lands where they would go together, in heaven and in hell. Therese waited. Then as she was about to go to her, Carol saw her, seemed to stare at her incredulously a moment while Therese watched the slow smile growing, before her arm lifted suddenly, her hand waved a quick, eager greeting that Therese had never seen before. Therese walked toward her.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“But when they kissed goodnight in bed, Therese felt their sudden release, that leap of response in both of them, as if their bodies were of some materials which put together inevitably created desire.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“An inarticulate anxiety, a desire to know, know anything, for certain, had jammed itself in her throat so for a moment she felt she could hardly breathe. Do you think, do you think, it began. Do you think both of us will die violently someday, be suddenly shut off? But even that question wasn’t definite enough. Perhaps it was a statement after all: I don’t want to die yet without knowing you. Do you feel the same way, Carol? She could have uttered the last question, but she could not have said all that went before it.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“Was it love or wasn't it that she felt for Carol? And how absurd it was that she didn't even know. She had heard about girls falling in love, and she knew what kind of people they were and what they looked like. Neither she nor Carol looked like that. Yet the way she felt about Carol passed all the tests for love and fitted all the descriptions.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“But Carol had not betrayed her. Carol loved her more than she loved her child. That was part of the reason why she had not promised.

She was gambling now as she had gambled on getting everything from the detective that day on the road, and she lost then, too. And now she saw Carol's face changing, saw the little signs of astonishment and shock so subtle that perhaps only she in the world could have noticed them, and Therese could not think for a moment.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“Happiness was like a green vine spreading through her, stretching fine tendrils, bearing flowers through her flesh. She had a vision of a pale-white flower, shimmering as if seen in darkness, or through water. Why did people talk of heaven, she wondered.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“It was easy, after all, simply to open the door and escape. It was easy, she thought, because she was not really escaping at all.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“She tried to keep her voice steady, but it was pretense, like pretending self-control when something you loved was dead in front of your eyes. They would have to separate here.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“She had seen just now what she had only sensed before, that the whole world was ready to be their enemy, and suddenly what she and Carol had together seemed no longer love or anything happy but a monster between them, with each of them caught in a fist.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“A kiss, for instance, is not to be minimized, or its value judged by anyone else. I wonder do these men grade their pleasure in terms of whether their actions produce a child or not, and do they consider them more pleasant if they do. It is a question of pleasure after all, and what’s the use of debating the pleasure of an ice cream cone versus a football game — or a Beethoven quartet versus the Mona Lisa. I’ll leave that to the philosophers.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“At any rate, Therese thought, she was happier than she ever had been before. And why worry about defining everything?”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“What a strange girl you are.”

“Why?”

“Flung out of space,” Carol said.”

― Patricia Highsmith

“Kick me out, she thought. What was in or out? How did one kick out an emotion?”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“She was conscious of the moments passing like irrevocable time, irrevocable happiness, for in these last seconds she might turn and see the face she would never see again.”

― Patricia Highsmith, Carol

“I think friendships are the result of certain needs that can be completely hidden from both people, sometimes hidden forever.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“I'm not melancholic,' she protested, but the thin ice was under her feet again, the uncertainties. or was it that she always wanted a little more than she had, no matter how much she had?”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“I think of a sun like Beethoven, a wind like Debussy, and birdcalls like Stravinsky. But the tempo is all mine.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“Though all we have known is only a beginning.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“An inarticulate anxiety, a desire to know, know anything, for certain, had jammed itself in her throat so for a moment she felt she could hardly breathe. Do you think, do you think, it began. Do you think both of us will die violently someday, be suddenly shut off? But even that question wasn’t definite enough. Perhaps it was a statement after all: I don’t want to die yet without knowing you. Do you feel the same way, Carol? She could have uttered the last question, but she could not have said all that went before it.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“Was it love or wasn't it that she felt for Carol? And how absurd it was that she didn't even know. She had heard about girls falling in love, and she knew what kind of people they were and what they looked like. Neither she nor Carol looked like that. Yet the way she felt about Carol passed all the tests for love and fitted all the descriptions.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“But Carol had not betrayed her. Carol loved her more than she loved her child. That was part of the reason why she had not promised.

She was gambling now as she had gambled on getting everything from the detective that day on the road, and she lost then, too. And now she saw Carol's face changing, saw the little signs of astonishment and shock so subtle that perhaps only she in the world could have noticed them, and Therese could not think for a moment.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“Happiness was like a green vine spreading through her, stretching fine tendrils, bearing flowers through her flesh. She had a vision of a pale-white flower, shimmering as if seen in darkness, or through water. Why did people talk of heaven, she wondered.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“It was easy, after all, simply to open the door and escape. It was easy, she thought, because she was not really escaping at all.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“She tried to keep her voice steady, but it was pretense, like pretending self-control when something you loved was dead in front of your eyes. They would have to separate here.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“She had seen just now what she had only sensed before, that the whole world was ready to be their enemy, and suddenly what she and Carol had together seemed no longer love or anything happy but a monster between them, with each of them caught in a fist.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“A kiss, for instance, is not to be minimized, or its value judged by anyone else. I wonder do these men grade their pleasure in terms of whether their actions produce a child or not, and do they consider them more pleasant if they do. It is a question of pleasure after all, and what’s the use of debating the pleasure of an ice cream cone versus a football game — or a Beethoven quartet versus the Mona Lisa. I’ll leave that to the philosophers.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“At any rate, Therese thought, she was happier than she ever had been before. And why worry about defining everything?”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“What a strange girl you are.”

“Why?”

“Flung out of space,” Carol said.”

― Patricia Highsmith

“Kick me out, she thought. What was in or out? How did one kick out an emotion?”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“She was conscious of the moments passing like irrevocable time, irrevocable happiness, for in these last seconds she might turn and see the face she would never see again.”

― Patricia Highsmith, Carol

“I think friendships are the result of certain needs that can be completely hidden from both people, sometimes hidden forever.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“I'm not melancholic,' she protested, but the thin ice was under her feet again, the uncertainties. or was it that she always wanted a little more than she had, no matter how much she had?”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“I think of a sun like Beethoven, a wind like Debussy, and birdcalls like Stravinsky. But the tempo is all mine.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“Though all we have known is only a beginning.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

“I know you have it in you, Guy," Anne said suddenly at the end of a silence, "the capacity to be terribly happy.”

― Patricia Highsmith, Strangers on a Train

― Patricia Highsmith, Strangers on a Train

“I like to drink when I travel. It enhances things, don’t you think?”

― Patricia Highsmith, Strangers on a Train

“I tell him his business, all business, is legalized throat-cutting, like marriage is legalized fornication.”

― Patricia Highsmith, Strangers on a Train

― Patricia Highsmith, Strangers on a Train

“I tell him his business, all business, is legalized throat-cutting, like marriage is legalized fornication.”

― Patricia Highsmith, Strangers on a Train

“Honestly, I don't understand why people get so worked up about a little murder!”

― Patricia Highsmith, Ripley Under Ground

― Patricia Highsmith, Ripley Under Ground

“I won't ever set the world on fire as a painter,' Dickie said, 'but I get a great deal of pleasure out of it.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley

“He liked the fact that Venice had no cars. It made the city human. The streets were like veins, he thought, and the people were the blood, circulating everywhere.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley

― Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley

“And everything was made of paper: sentences, pardons, pleas, bad records, demerits, proof of guilt, but never, it seemed, proof of innocence. If there were no paper, Carter felt, the entire judicial system would collapse and disappear.”

― Patricia Highsmith, The Glass Cell

“I had depressing thoughts that the theme, even though I had thought of it, was better than I was as a writer. Henry James or Thomas Mann could easily write it, but not I. 'I'm thinking of writing it from the point of view of someone at the hotel who observes her,' I said, but this did not fill me with much hope. Then my friend, who is not a writer, suggested I try it from the omniscient author's point of view.”

― Patricia Highsmith, Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction

“Happiness was a little like flying, she thought, like being a kite. It depended on how much one let the string out.”

― Patricia Highsmith

“I had depressing thoughts that the theme, even though I had thought of it, was better than I was as a writer. Henry James or Thomas Mann could easily write it, but not I. 'I'm thinking of writing it from the point of view of someone at the hotel who observes her,' I said, but this did not fill me with much hope. Then my friend, who is not a writer, suggested I try it from the omniscient author's point of view.”

― Patricia Highsmith, Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction

“Happiness was a little like flying, she thought, like being a kite. It depended on how much one let the string out.”

― Patricia Highsmith

Creative writing lessons

from Patricia Highsmith

Highsmith’s book Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction is an inspiring primer for budding psycho-crime novelists

Sam Jordison

Tuesday 16 June 2015 17.19 BST

Earlier this month, Reading group contributor Mmeritt1 recommended Patricia Highsmith’s book Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction. It is “edifying and inspirational”, s/he wrote. And s/he is absolutely right.

The book is as unusual as you might expect and hope for from Patricia Highsmith. An elegant creative writing guide, it’s also a goldmine for anyone hoping for insight into The Talented Mr Ripley – and its author.

Highsmith points out in the book that The Talented Mr Ripley begins with an “almost but not quite incredible” coincidence. It’s quite some chance that the father of Dickie Greenleaf selects Tom Ripley, “a potential murderer”, to bring his son home.

As soon as I read that I could see that it was all too true. What astonishing ill fortune that Greenleaf Snr should select a sociopath – who barely knows his son – as the person to help him. And that he should pay for that sociopath to go all the way to Italy from New York and live with his son. I want to write that it stretches credulity; and yet I have to admit that it didn’t stretch mine at all. Motoring through the pages, I accepted the coincidence as fine and natural; the story’s details are presented in such a reasonable, matter-of-fact way, and the reader zips along, happily snapped into a mantrap of narration.

The book is full of direct and clear explanations of the mechanics of plotting and how best to use chance as a device. Such passages also demonstrate Highsmith’s magic – her power to compel you to read on and forget about how unlikely it all is. Although, if you’re hoping for tips about casting such spells yourself, Plotting and Writing A Suspense Thriller may sometimes make for depressing reading. Often, as much as providing a step-by-step guide, it demonstrates how impossible it is to walk in Highsmith’s shoes.

You might be able to follow her writing method of “mentally as well as physically sitting on the edge of my chair” while composing your thriller (done because Ripley is a young man on the edge of his chair - “if he is sitting down at all”). Good luck, however, if you want to create this kind of alchemy:

“By thinking myself inside the skin of [Ripley], my own prose became more self-assured than it logically should have been … No book was easier for me to write and I often had the feeling Ripley was writing it and I was merely typing.”

Plenty of the rest of her advice is similarly hard to follow – unless, like Highsmith, you happen to be a major talent. “The setting and the people must be seen as clearly as a photograph,” she advises. Well, yes. She also notes that a writer “should sense when something is wrong, as quickly as a mechanic hears a wrong noise in an engine, and he should correct it before it becomes worse”. That’s true, and irrefutably good advice. But it’s no more or less useful than Mike Tyson telling you that you need to move faster, dodge smarter and hit harder. It might work for him…

In spite of her modest tone, much of this book reads like a showcase of a master magician’s tricks. But it’s worth reading for other reasons, not least its delightful idiosyncrasy. “I cannot think of anything worse or more dangerous than to discuss my work with another writer,” says Highsmith. Doing so seems to be one of the peculiar enjoyments of the French, she explains.

Elsewhere, she writes: “I create things out of boredom with reality and with the sameness of routine and objects around me.” That’s some insight into the languid minds of so many of her characters - and the way she flings them to far flung places and strange situations. Also, into how detached she could be. How many people here suffer from reality boredom?

Another moment of telling self-revelation comes when (and no surprises here if you’ve been following this month’s Reading group) she says that she doesn’t enjoy letting justice catch up with her criminals. She “rather” likes them and finds them “extremely interesting, unless they are monotonously and stupidly brutal”.

But please don’t get the impression that Highsmith is as amoral as her subjects. One page later she points out how strange it is that the public likes to see the law triumph – but has no issue with brutality. “Sleuth-heroes” can beat women, be brutal and sexually unscrupulous, but the public will still cheer them on because they are chasing “something worse than themselves, presumably”.

The impression you get of Highsmith is of a complicated, roving intelligence: clear-sighted, determined and not at all concerned with trying to live a conventional life. The book is correspondingly eccentric. Yet while it doesn’t have the usual sets of rules, suggestions and markers you might expect from a creative writing handbook, by the end you realise that this is a singularly useful volume. There’s hard practical advice here from someone who has a fine understanding of plotting, motivation, what to “show” and not tell, how to keep things moving forward and how and where to place a climax.

There is further gold on what she terms “thickening” the plot – adding complications to ensure that things remain interesting. (Examples from The Talented Mr Ripley would be the unexpected arrival of Freddie Miles in Tom/Dickie’s flat in Rome, and Dickie’s father’s decision to hire a detective late on in the novel.) She also cuts through the complications surrounding point of view. Don’t dwell on the question, says Highsmith: just think about whose eyes the story is looking through, and whether the story would be better told from someone else’s point of view. She notes that keeping the focus on Ripley, for instance, increases intensity. Possibly that’s another pep-talk from the Mike Tyson boxing school – but it points to her broader ideal of avoiding complications and just trying to do the practical thing.

And in case you are still worried that this is a book that will work only for the unusually talented, Highsmith is also tremendously reassuring about her own struggles and unfinished projects. Not to mention financial concerns, even deep into a successful career: “The eternal maneuverings one has to perform in order to exist on an irregular and often inadequate income … the insecurity that is the very air writers breathe.”

She’s possibly at her best when discussing failure. She talks about several projects of her own that she hasn’t finished - books where she became too involved with small irrelevant details, plots that didn’t work out, books that didn’t sell. In fact, she explains neatly why there’s no such thing as failure in writing, just the accumulation of experience. “A writer should not think he is bad or finished [if a book fails to get to market] … Every failure teaches something. You should have the feeling, as every experienced writer has, that there are more ideas where that one came from, more strength where the first strength came from, and that you are inexhaustible as long as you are alive.”

Keep going, in other words.

Patricia Highsmith

A ROMANCE OF THE 1950S

A MEMOIR BY MIRIJANE MEAKER

I came across Marijane Meaker’s book Carol in a Thousand Cities by accident in 1972, when I was 19 and living in Ceylon. I remember that it sucked the air out of my lungs to find out that there was a world far away in the West where exotic beings called lesbians actually existed in numbers — and as a social group. Of course it was not their exoticism that stunned me, but their familiarity to me — and their separate existence as a coherent phenomenon — a social entity — a possibility of being alive and living in “real” life — as with a band of angels and in a heaven on earth.

It took several more years — more than three decades — before I was to run into Meaker again, and found myself launched once more on the fascinating journey exploring so called lesbian pulps. Marijane Meaker, a.k.a Ann Aldrich a.k.a Vin Packer a.k.a M.E. Kerr (Meaker) was a pioneer of lesbian fiction, and she is still wonderfully alive and kicking, as is the illustrious Ann Bannon. By then, Meaker’s world no longer represented for me a heaven on earth, but something even greater — an earthy life in which earthly aspirations were possible for lesbians.

I started out by reading Meaker’s ‘Highsmith’ , the fantastic memoir of her ’50’s love affair with Patricia Highsmith. That led inexorably to ‘We Too Must Love,’ ‘Spring Fire’ (published under the name Vin Packer) and a blissful re-read of ‘Carol in a Thousand Cities’ a line taken verbatim from the last paragraphs of Highsmith’s famous lesbian love story(and the first one said to have a happy ending), ‘The Price of Salt’.

In Highsmith I found for the first time in a long time a book I could not put down. In it Meaker writes with warm sentiment and without sentimentality, about her love affair with Patricia Highsmith. I can’t quite put my finger on what it is about Meaker’s prose that so immediately evokes the flavour of the ‘fifties. I see rising up before my eyes the photographs of George Marks and Chaloner Woods, — women in Massey suits and print dresses and summer coats, and I hear the romantic, evocative music of Jeri Southern, Chris Connor, Jo Stafford….

In Highsmith I found for the first time in a long time a book I could not put down. In it Meaker writes with warm sentiment and without sentimentality, about her love affair with Patricia Highsmith. I can’t quite put my finger on what it is about Meaker’s prose that so immediately evokes the flavour of the ‘fifties. I see rising up before my eyes the photographs of George Marks and Chaloner Woods, — women in Massey suits and print dresses and summer coats, and I hear the romantic, evocative music of Jeri Southern, Chris Connor, Jo Stafford….

Despite the stark repressiveness of that time in U. S History of highly neuroticised social oppression, (it was the era of McCarthyism, the cold war, and psychoanalysis and sexism) — and who knows, perhaps exactly because of it — there was a social cohesiveness in the gay and lesbian world now long since disappeared. For me It only appears now in the fiction of the day. This was the world which provided the necessary back-drop for the kind of chance meetings which are now a part of our lesbian history. It was the era of lesbian bars where women went to meet each other, drink, socialise, catch up with the world, and fall in love. L’s was such a bar, and it was where  Meaker and Highsmith met for the first time, and had there not been such a place, they would probably not have met at all. But meet they did, in that hidden world of the fascinating denizens of the ‘fifties New York, lesbians in secret enclaves which survived and thrived despite the tensions and dramas of an era in American history filled with paranoia and social anxiety.

Meaker and Highsmith met for the first time, and had there not been such a place, they would probably not have met at all. But meet they did, in that hidden world of the fascinating denizens of the ‘fifties New York, lesbians in secret enclaves which survived and thrived despite the tensions and dramas of an era in American history filled with paranoia and social anxiety.

Meaker and Highsmith met for the first time, and had there not been such a place, they would probably not have met at all. But meet they did, in that hidden world of the fascinating denizens of the ‘fifties New York, lesbians in secret enclaves which survived and thrived despite the tensions and dramas of an era in American history filled with paranoia and social anxiety.

Meaker and Highsmith met for the first time, and had there not been such a place, they would probably not have met at all. But meet they did, in that hidden world of the fascinating denizens of the ‘fifties New York, lesbians in secret enclaves which survived and thrived despite the tensions and dramas of an era in American history filled with paranoia and social anxiety.

It surprised me to learn that Meaker’s Highsmith was affectionate and publicly demonstrative of her affection — something extremely rare in that hetero-totalitarian time. It would seem that Highsmith’s particular brand of internalised homophobia was a writerly and intellectual construct, and it never flooded the banks of their internal reservoir into the territory of her love affairs and relationships. Meaker says Highsmith ” would hold girls’ hands in the street, the supermarket, in restaurants.”

For me the saddest part of this relationship is of course its failure as a friendship when the two met again in the ‘eighties, a failure I think was not at all inevitable, but for Highsmith’s incomprehensible inner compulsion which made her unable to desist from repeatedly expressing her racist and anti-semitic feelings and views. This in the end caused Meaker to shut down emotionally with her, and it forestalled any possibility of emotional re-connection or a renewal of their former love.

Though it is impossible to make conjectures or claims on behalf of the subconscious — one’s own or another’s – it might be that Highsmith may have chosen this tactic in order to avoid the pain of an inevitable separation with Meaker. Meaker is quite explicit about her disagreements with Highsmith, but somehow, their breakup is strangely inexplicable. Meaker does not hesitate to make herself the object of her own irony. She was reactive and volatile while Highsmith was reserved and restrained and conciliatory. One has to admire Meaker for her forthrightness — she is honest and unsparing of herself in revealing what she herself said and did in order to precipitate the end of their affair. The two of them seem to have been each other’s only loves, and the loss of that love had devastating consequences for Highsmith.

Though it is impossible to make conjectures or claims on behalf of the subconscious — one’s own or another’s – it might be that Highsmith may have chosen this tactic in order to avoid the pain of an inevitable separation with Meaker. Meaker is quite explicit about her disagreements with Highsmith, but somehow, their breakup is strangely inexplicable. Meaker does not hesitate to make herself the object of her own irony. She was reactive and volatile while Highsmith was reserved and restrained and conciliatory. One has to admire Meaker for her forthrightness — she is honest and unsparing of herself in revealing what she herself said and did in order to precipitate the end of their affair. The two of them seem to have been each other’s only loves, and the loss of that love had devastating consequences for Highsmith.

One cannot evade the feeling that Highsmith’s virulence in this regard is overdone, and that she expressed these unsavoury views in order to elicit a specific response — perhaps something as small as a nominal agreement. It may have been a gambit to test the degree to which she was loved and accepted — not just for her goodness and virtues, but despite her faults and flaws — but it was a response that never came from Meaker. Perhaps if Meaker had realised there was no point in trying either to make Highsmith reform or to repudiate her view, there might have been a different ending to the story of their relationship. After all, these were views which were not aired in her writing, and they were for the most part private, and not followed-up by violent actions. No one was harmed by them. Put them into the mouth of a Nazi, or a member of the K.K.K or an Islamist, and their power to devastate would be incalculable, but coming from the mouth of a mild-mannered old lesbian writer, who is furthermore much given to  drinking, they seem more dismissive than dangerous. Highsmith was to become an old crank, but one gets the sense that there was a great mind and a responsive heart beneath the distant and forbidding manner

drinking, they seem more dismissive than dangerous. Highsmith was to become an old crank, but one gets the sense that there was a great mind and a responsive heart beneath the distant and forbidding manner

drinking, they seem more dismissive than dangerous. Highsmith was to become an old crank, but one gets the sense that there was a great mind and a responsive heart beneath the distant and forbidding manner

drinking, they seem more dismissive than dangerous. Highsmith was to become an old crank, but one gets the sense that there was a great mind and a responsive heart beneath the distant and forbidding manner

Highsmith was brought up a Southerner and a Texan, and her unexamined racism may have been felt by her to be a part of her which stood for her Southern identity. Her racism never extended beyond words, (she had friendships and affairs with Jewish women, and Arthur Koestler and his wife Cynthia Jefferies were close friends) and her fulminations were never virulent. In fact they were so manifestly pointless that one wishes they could have simply been ignored. Instead and regrettably they made a renewed relationships with Meaker impossible.

The Talented Miss Highsmith, Joan Schenkar’s biography of Highsmith shows her to be a racist anti-semitic miserly monster with no real feelings for anyone but herself, but –despite acknowledging and being distressed by Highsmith’s anti-semiticism, Meaker portrays her as loving and sensitive, with the emotional restraint under duress that can never be acquired and that can only either be inherent, or the result of good breeding. I cannot reconcile the image of Highsmith as a psychopath, presented by Joan Schenkar, with Meake’s portrayal of this fabulous dark-haired butch with her W29 L34 Levis with their sharp creases and her crisply ironed white shirts. This is a woman who was charming, romantic, affectionate, who at the last moment cancelled her plans to leave  the country because she regretted having to cancel a dinner date she had planned with Meaker to celebrate their two month anniversary. Meaker describes a getaway in the summer of ’59 after Highsmith had given her a gold wedding band (bought in an antique store) in acknowledgement of their relationship, when “there were blissful days ahead in Fair Harbor: making love, sunbathing, reading, walking along the shore. cooking dinner for each other, and lingering into the night having drinks and listening to music” and at other times (when a late visit to Janet Flanner, then 67, and her lover Natalia Murray at Fair Harbour did not result in the expected invitation to stay overnight) sleeping in each other’s arms in the rain on the beach.

the country because she regretted having to cancel a dinner date she had planned with Meaker to celebrate their two month anniversary. Meaker describes a getaway in the summer of ’59 after Highsmith had given her a gold wedding band (bought in an antique store) in acknowledgement of their relationship, when “there were blissful days ahead in Fair Harbor: making love, sunbathing, reading, walking along the shore. cooking dinner for each other, and lingering into the night having drinks and listening to music” and at other times (when a late visit to Janet Flanner, then 67, and her lover Natalia Murray at Fair Harbour did not result in the expected invitation to stay overnight) sleeping in each other’s arms in the rain on the beach.

the country because she regretted having to cancel a dinner date she had planned with Meaker to celebrate their two month anniversary. Meaker describes a getaway in the summer of ’59 after Highsmith had given her a gold wedding band (bought in an antique store) in acknowledgement of their relationship, when “there were blissful days ahead in Fair Harbor: making love, sunbathing, reading, walking along the shore. cooking dinner for each other, and lingering into the night having drinks and listening to music” and at other times (when a late visit to Janet Flanner, then 67, and her lover Natalia Murray at Fair Harbour did not result in the expected invitation to stay overnight) sleeping in each other’s arms in the rain on the beach.

the country because she regretted having to cancel a dinner date she had planned with Meaker to celebrate their two month anniversary. Meaker describes a getaway in the summer of ’59 after Highsmith had given her a gold wedding band (bought in an antique store) in acknowledgement of their relationship, when “there were blissful days ahead in Fair Harbor: making love, sunbathing, reading, walking along the shore. cooking dinner for each other, and lingering into the night having drinks and listening to music” and at other times (when a late visit to Janet Flanner, then 67, and her lover Natalia Murray at Fair Harbour did not result in the expected invitation to stay overnight) sleeping in each other’s arms in the rain on the beach.

In an act of selflessness and love, Meaker had given up her wonderful little apartment in Manhattan, and the life she had carefully constructed there in order to move together to a property in Bucks County Pa, on the Delaware canal. This was where their relationship took root, and grew, and finally came undone. And that is were I find the core of this book to lie. The real sub-text is a documentation of the fleetingness of love relationships even when love itself is strong.

Perhaps the more significance a personal love has in life, the more viable are the seeds of its own destruction, and the more inevitable the final  disaster.

disaster.

disaster.

disaster.

There is a poem by Robert Graves which speaks of a month in mid-summer and the course of poetic love-

The demon who throughout our late estrangement,

Followed with malice in my footsteps, often

Making as to stumble . . .

Yet,

We both know well he was the same demon,

Arch-enemy of rule and calculation,

Who lives for our love, being created from it….

Followed with malice in my footsteps, often

Making as to stumble . . .

Yet,

We both know well he was the same demon,

Arch-enemy of rule and calculation,

Who lives for our love, being created from it….

There is something I refer to as ‘The Heathcliff Factor’, when the wellspring of love is choked and thwarted on one who needs love even more than she or he wants it, there is a reflexive destructiveness and a hardening of the self that is the frequent result of buried pain. A sort of malignancy shoots out of the depths like some poisonous plume, which only a stable and reliable love can hold in check. When that love is gone, it erupts and moves across the surface of life like a pyroclastic flow, scorching and killing everything before it.

When one recalls love in one’s later years, only the best — and the worst — can elicit the effort of recounting, and Highsmith, this beautifully written and stylishly evoked chronicle of self-revelation of the love of a lifetime, bears this out. It is sobering and saddening precisely because of how skillfully and irresistibly the past is made to make its way to the present, and to a tacit conclusion about the nature of love. Meaker and Highsmith seem to me to have been, in the end, each others’ ‘one and only’. And yet, though love went on surviving, the relationship could not. Told from Meaker’s point of view, she always feared that Highsmith would yield to the temptation to have affairs with other women. Though there was nothing untrustworthy about Highsmith (Meaker mentions only one dishonest act of Highsmith’s, the appropriation of a roll of film, which after all contained her own image), she succumbed to the temptation to snoop in Highsmith’s papers, interfere with her mail, and stalk her suspected lover. In fact, It is Meaker who stepped out on her live- in lover when she first met Highsmith. She kept the affair secret until she left New York to move with Highsmith to Pennsylvania The course of true love runs by default: like water it is ruled by gravity, and seeks its lowest level, It is willed into turbulence and in the absence of movement it reverts to inertia. In the case of Highsmith and Meaker, it was something between the two that put an end to their association.

When one recalls love in one’s later years, only the best — and the worst — can elicit the effort of recounting, and Highsmith, this beautifully written and stylishly evoked chronicle of self-revelation of the love of a lifetime, bears this out. It is sobering and saddening precisely because of how skillfully and irresistibly the past is made to make its way to the present, and to a tacit conclusion about the nature of love. Meaker and Highsmith seem to me to have been, in the end, each others’ ‘one and only’. And yet, though love went on surviving, the relationship could not. Told from Meaker’s point of view, she always feared that Highsmith would yield to the temptation to have affairs with other women. Though there was nothing untrustworthy about Highsmith (Meaker mentions only one dishonest act of Highsmith’s, the appropriation of a roll of film, which after all contained her own image), she succumbed to the temptation to snoop in Highsmith’s papers, interfere with her mail, and stalk her suspected lover. In fact, It is Meaker who stepped out on her live- in lover when she first met Highsmith. She kept the affair secret until she left New York to move with Highsmith to Pennsylvania The course of true love runs by default: like water it is ruled by gravity, and seeks its lowest level, It is willed into turbulence and in the absence of movement it reverts to inertia. In the case of Highsmith and Meaker, it was something between the two that put an end to their association.

Highsmith possessed an unerring sense of her own integrity which led her to reject received wisdom and received values, particularly of the sort that Meaker subscribed to, in the area of the kinds of psychological analysis of homosexuality that Meaker (at least in her fiction) appeared to uphold. Highsmith was sure-footed and confident about her own sexual orientation and practices — a true butch — whereas Meaker was ambivalent about sexual ‘norms’, and was a Freudian apologist of sorts. She bowed under her publisher’s pressure to end her lesbian novels badly (for the lesbians involved) whereas Highsmith contrived herself a way out of a similar stricture. Though both women were paranoid about being ‘outed’ (and who, being mindful of their times, could blame them?) Highsmith’s personal reticence and secrecy unsettled Meaker and drover her to succumb to her own insecurities and to violations of Highsmith’s privacy.

received wisdom and received values, particularly of the sort that Meaker subscribed to, in the area of the kinds of psychological analysis of homosexuality that Meaker (at least in her fiction) appeared to uphold. Highsmith was sure-footed and confident about her own sexual orientation and practices — a true butch — whereas Meaker was ambivalent about sexual ‘norms’, and was a Freudian apologist of sorts. She bowed under her publisher’s pressure to end her lesbian novels badly (for the lesbians involved) whereas Highsmith contrived herself a way out of a similar stricture. Though both women were paranoid about being ‘outed’ (and who, being mindful of their times, could blame them?) Highsmith’s personal reticence and secrecy unsettled Meaker and drover her to succumb to her own insecurities and to violations of Highsmith’s privacy.

received wisdom and received values, particularly of the sort that Meaker subscribed to, in the area of the kinds of psychological analysis of homosexuality that Meaker (at least in her fiction) appeared to uphold. Highsmith was sure-footed and confident about her own sexual orientation and practices — a true butch — whereas Meaker was ambivalent about sexual ‘norms’, and was a Freudian apologist of sorts. She bowed under her publisher’s pressure to end her lesbian novels badly (for the lesbians involved) whereas Highsmith contrived herself a way out of a similar stricture. Though both women were paranoid about being ‘outed’ (and who, being mindful of their times, could blame them?) Highsmith’s personal reticence and secrecy unsettled Meaker and drover her to succumb to her own insecurities and to violations of Highsmith’s privacy.

received wisdom and received values, particularly of the sort that Meaker subscribed to, in the area of the kinds of psychological analysis of homosexuality that Meaker (at least in her fiction) appeared to uphold. Highsmith was sure-footed and confident about her own sexual orientation and practices — a true butch — whereas Meaker was ambivalent about sexual ‘norms’, and was a Freudian apologist of sorts. She bowed under her publisher’s pressure to end her lesbian novels badly (for the lesbians involved) whereas Highsmith contrived herself a way out of a similar stricture. Though both women were paranoid about being ‘outed’ (and who, being mindful of their times, could blame them?) Highsmith’s personal reticence and secrecy unsettled Meaker and drover her to succumb to her own insecurities and to violations of Highsmith’s privacy.

Even allowing for the self-preserving evasion endemic to every biography, one cannot but be impressed with Meaker’s clarity, and her slightly mocking tone of self-deprecation.  There is a wryness here that stands as a guarantor that not too much sweetener has been added to cover the bitter taste of old memories of loss and of love gone awry. One feels that this was a loss that was irrecoverable to both women, and the sound of ‘if only’ seems to echo in the wind. This is a book I will always be glad I read. In Meaker’s book, Highsmith is presented sympathetically and respectfully. This is by no means the prurient tell-all revelation filled with gratuitously graphic details of love-lives. The intensity and fire which existed between the two women is clearly and sparsely communicated, which in itself is a remarkable achievement. It is not as complete as Andrew Wilson’sBeautiful Shadow and not as bitter as Joan Schenkar’s The Talented Miss. Highsmith. It is in a sense the most personal and kind of Highsmith’s biographies.

There is a wryness here that stands as a guarantor that not too much sweetener has been added to cover the bitter taste of old memories of loss and of love gone awry. One feels that this was a loss that was irrecoverable to both women, and the sound of ‘if only’ seems to echo in the wind. This is a book I will always be glad I read. In Meaker’s book, Highsmith is presented sympathetically and respectfully. This is by no means the prurient tell-all revelation filled with gratuitously graphic details of love-lives. The intensity and fire which existed between the two women is clearly and sparsely communicated, which in itself is a remarkable achievement. It is not as complete as Andrew Wilson’sBeautiful Shadow and not as bitter as Joan Schenkar’s The Talented Miss. Highsmith. It is in a sense the most personal and kind of Highsmith’s biographies.

There is a wryness here that stands as a guarantor that not too much sweetener has been added to cover the bitter taste of old memories of loss and of love gone awry. One feels that this was a loss that was irrecoverable to both women, and the sound of ‘if only’ seems to echo in the wind. This is a book I will always be glad I read. In Meaker’s book, Highsmith is presented sympathetically and respectfully. This is by no means the prurient tell-all revelation filled with gratuitously graphic details of love-lives. The intensity and fire which existed between the two women is clearly and sparsely communicated, which in itself is a remarkable achievement. It is not as complete as Andrew Wilson’sBeautiful Shadow and not as bitter as Joan Schenkar’s The Talented Miss. Highsmith. It is in a sense the most personal and kind of Highsmith’s biographies.

There is a wryness here that stands as a guarantor that not too much sweetener has been added to cover the bitter taste of old memories of loss and of love gone awry. One feels that this was a loss that was irrecoverable to both women, and the sound of ‘if only’ seems to echo in the wind. This is a book I will always be glad I read. In Meaker’s book, Highsmith is presented sympathetically and respectfully. This is by no means the prurient tell-all revelation filled with gratuitously graphic details of love-lives. The intensity and fire which existed between the two women is clearly and sparsely communicated, which in itself is a remarkable achievement. It is not as complete as Andrew Wilson’sBeautiful Shadow and not as bitter as Joan Schenkar’s The Talented Miss. Highsmith. It is in a sense the most personal and kind of Highsmith’s biographies.

This is an entry from one of Highsmith’s private journals. It shows a very different aspect of her being, completely unlike her guarded and rebarbative public persona. This is the Highsmith, I think, with whom Meaker fell in love, and who fell in love with her in return.

“Even in his arms dancing, one feels her in one’s arms dancing. The brain dully occupied with him, dreams with a clarity and a sentiment (not being controlled by its logical mechanism) that stifles the breath, bringing tears. One dreams of dancing with her, in public, of a stolen kiss more freely given and taken than any heretofore, in public. One is utterly crushed with the thought– which had become reality now, here – that one is for eternity an imprisoned soul in one’s present body…One knows then too,. and perhaps this is no small portion of the sadness, that life with any man is no life at all. For the soul, with its infallible truth and rightness, its logic derived from perfect purity, cries for her one love, her!”

“Even in his arms dancing, one feels her in one’s arms dancing. The brain dully occupied with him, dreams with a clarity and a sentiment (not being controlled by its logical mechanism) that stifles the breath, bringing tears. One dreams of dancing with her, in public, of a stolen kiss more freely given and taken than any heretofore, in public. One is utterly crushed with the thought– which had become reality now, here – that one is for eternity an imprisoned soul in one’s present body…One knows then too,. and perhaps this is no small portion of the sadness, that life with any man is no life at all. For the soul, with its infallible truth and rightness, its logic derived from perfect purity, cries for her one love, her!”

Patricia Highsmith

THE PRICE OF SALT

A sexual ‘deviant’ snatches a motherless teenager away from her normal life, and together they set off for a car ride across the country. This is the context of  their (in those times) transgressive sexual adventure. There is a sinister man in surreptitious and tenacious pursuit of them, and his intentions are inimical to their happiness.

their (in those times) transgressive sexual adventure. There is a sinister man in surreptitious and tenacious pursuit of them, and his intentions are inimical to their happiness.

their (in those times) transgressive sexual adventure. There is a sinister man in surreptitious and tenacious pursuit of them, and his intentions are inimical to their happiness.

their (in those times) transgressive sexual adventure. There is a sinister man in surreptitious and tenacious pursuit of them, and his intentions are inimical to their happiness.

Perhaps this sounds familiar. It is clear that when he wrote ‘Lolita’,(published in 1955), Vladimir Nabokov purloined a sly fistful of leaves out of Patricia Highsmith’s 1952 novel ‘The Price of Salt’ published under the pseudonym of Claire Morgan.

Though Highsmith’s terse style is antithetical to Nabokov’s lushly intoxicating prose and convoluted machinations of plot, her second novel, (the first being ‘Strangers on a Train’) is no less iconic for being the first piece of published lesbian fiction to have a happy ending.

The winter of ’48 found twenty seven year old Patricia Highsmith working in the toy department of Bloomingdales, when a beautiful woman dressed in a mink coat came in to buy a doll for her daughter. The cooly aristocratic woman was Kathleen Wiggins Senn. Highsmith was instantly stricken, and managed to memorise Mrs Senn’s name and address and send her a card. Senn never responded, and by the time ‘The Price of Salt’ was published in 1952, she had committed suicide. The two never met.

Highsmith, almost swooning from the brush with her potent Muse, and infected with the germs of both an incipient novel as well as an eruptive disease, rushed home, and in a state of physical as well as emotional fever (she was coming down with chicken pox) wrote the entire outline of her feverish fantasy of wish-fulfillment ‘The Price of Salt’. This kind of unsettling slipping away of the mind that leaves one looking foolish in the eyes of the enchanter when one would least wish it, often turns the lock of the secret door from which myths and inspirations emerge.

In Highsmith’s novel Therese Belivet is a nineteen year old sales clerk in the toy department of Frankenbergs, when Carol Aird comes in to buy a doll for her daughter. Therese sends Mrs Aird a card, and Mrs Aird responds by suggesting that they meet. The degree and intensity of Therese’s estrangement from her boyfriend Richard runs parallel to the emergence of her developing affair with Carol. That the affair is excruciatingly slow to take shape, should not surprise us, coming from a writer who found engrossing the copulation of snails.

Carol is in the process of divorcing her husband Harge, and enmeshed in a custody battle for her young daughter Rindy,  when Therese and Carol impulsively decide to leave together and drive across the country in Carol’s car. In the midst of their travels they become aware that they are being tailed by a detective (hired by Harge) The detective has bugged their motel rooms with what Highsmith refers to as ‘a dictaphone’, and of course the evidence he has collected is harmful and incriminating. Incriminating too is a letter addressed to Carol Therese had placed in a book of poetry she was reading at Carol’s house and inadvertently left behind.

when Therese and Carol impulsively decide to leave together and drive across the country in Carol’s car. In the midst of their travels they become aware that they are being tailed by a detective (hired by Harge) The detective has bugged their motel rooms with what Highsmith refers to as ‘a dictaphone’, and of course the evidence he has collected is harmful and incriminating. Incriminating too is a letter addressed to Carol Therese had placed in a book of poetry she was reading at Carol’s house and inadvertently left behind.

when Therese and Carol impulsively decide to leave together and drive across the country in Carol’s car. In the midst of their travels they become aware that they are being tailed by a detective (hired by Harge) The detective has bugged their motel rooms with what Highsmith refers to as ‘a dictaphone’, and of course the evidence he has collected is harmful and incriminating. Incriminating too is a letter addressed to Carol Therese had placed in a book of poetry she was reading at Carol’s house and inadvertently left behind.

when Therese and Carol impulsively decide to leave together and drive across the country in Carol’s car. In the midst of their travels they become aware that they are being tailed by a detective (hired by Harge) The detective has bugged their motel rooms with what Highsmith refers to as ‘a dictaphone’, and of course the evidence he has collected is harmful and incriminating. Incriminating too is a letter addressed to Carol Therese had placed in a book of poetry she was reading at Carol’s house and inadvertently left behind.

The chastity of the relationship remains unchallenged until Carol and Therese are halfway through their travels, in Waterloo Iowa, but even after the abrupt interjection of sex, (implausible because until it happens there is no hint of it) the passion in this affair seems chilly, and fraught with the undercurrent of an ever present sense of incipient rejection. Carol acts superior to Therese, patronising her and alluding to her love as an ephemeral artifact of her youth and immaturity, and something which she will outgrow with age. Therese in turn exasperates Carol by frequently ignoring Carol’s questions, and communications between them are weighted with an underlying tension. Carol calls Therese insensitive – but is she really? or is this some of Highsmith’s almost autistic tin ear for sentiment which makes of this book that strange concoction – lovers who truthfully requite each others love, but express it with a marked insufficiency of warmth.

Curiously, this love has none of the unguarded openness which frequently emerges in the liquid depths of ‘falling in love’: There is no evidence of the repairing of damage and healing of wounds that accompanies mutual love. If there was tenderness here, I missed it, and both the falling in love, as well as the sex that finally accompanies it are fiats with no preamble. Sex between the two though intense and erotically charged, and described in almost hallucinatory terms, has no hint of yearning, and none of the ‘reluctance to let go’ which is love’s aftermath. Like the women themselves, it is abrupt both in beginning and end.

The reason for this otherwise inexplicable coldness could be a fascinating dynamic: Therese, the victim of an absent and rejecting mother, has fallen in love with another ‘absent mother’.

But Carol loves her daughter Rindy.

So, inevitably,in order for this love affair to be viable for Therese, Rindy, the legitimate occupant of the nest must be expelled, or else Therese would be in danger of becoming a mere step-child in this oedipal contest.

But Carol loves her daughter Rindy.

So, inevitably,in order for this love affair to be viable for Therese, Rindy, the legitimate occupant of the nest must be expelled, or else Therese would be in danger of becoming a mere step-child in this oedipal contest.

There is often a real risk of chronic insecurity and uncertainty when one’s new lover already has a child. Only someone who has had good and adequate mothering, which Therese did not get, could survive playing second fiddle in the affections of a lover. The almost palpable disconnect in the affair is Therese’s anxiety over being loved less than Rindy, and Carol’s conflicting feelings about the likelihood of having to forfeit her child if she is to keep her young lover.