DRAGON

Iman on David Bowie: ‘I didn't want to get into a relationship with somebody like him’Angie Bowie decides to stay in Celebrity Big Brother house after being told of David Bowie's death

FICCIONES

Triunfo Arciniegas / Diario / Ha muerto David Bowie

David Bowie / Preguntas

Casa de citas / David Bowie / Chica o chico

Casa de citas / David Bowie / Fuego

David Bowie / Preguntas

Casa de citas / David Bowie / Chica o chico

Casa de citas / David Bowie / Fuego

DE OTROS MUNDOS

Tony Scott / El ansia

Mick Jagger / Las relaciones sexuales con David Bowie y Carla Bruni

David Bowie / El devorador insaciable

Muere David Bowie a los 69 años

Iman llora la muerte de David Bowie

David Bowie / Con Ziggy Stardust llegó la ambigüedad

La importancia de llamarse David Bowie

Vuelve David Bowie (nunca se fue)

Franz Schubert / Piano Trio In E Flat / David Bowie

David Bowie / Cinco claves de su oscuro y retorcido nuevo disco

Iman y David Bowie / Eso que llaman amor

David Bowie murió sabiendo que iba a ser abuelo

Tony Scott / El ansia

Mick Jagger / Las relaciones sexuales con David Bowie y Carla Bruni

David Bowie / El devorador insaciable

Muere David Bowie a los 69 años

Iman llora la muerte de David Bowie

David Bowie / Con Ziggy Stardust llegó la ambigüedad

La importancia de llamarse David Bowie

Vuelve David Bowie (nunca se fue)

Franz Schubert / Piano Trio In E Flat / David Bowie

David Bowie / Cinco claves de su oscuro y retorcido nuevo disco

Iman y David Bowie / Eso que llaman amor

David Bowie murió sabiendo que iba a ser abuelo

PESSOA

RIMBAUD

DANTE

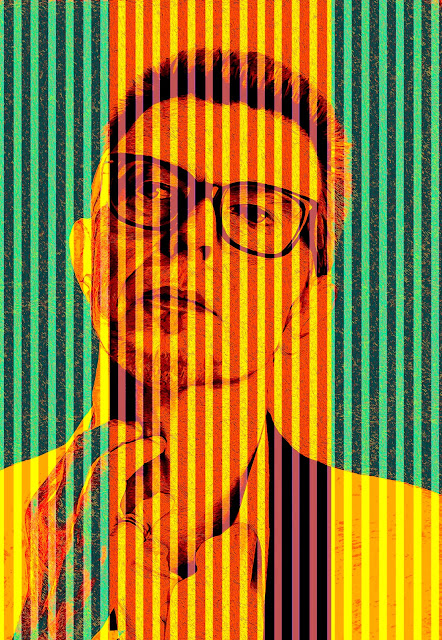

David Bowie

(1947 - 2016)

David Bowie was an English rock star known for dramatic musical transformations, including his character Ziggy Stardust. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996.

Synopsis

David Bowie was born in South London's Brixton neighborhood on January 8, 1947. His first hit was the song "Space Oddity" in 1969. The original pop chameleon, Bowie became a fantastical sci-fi character for his breakout Ziggy Stardust album. He later co-wrote "Fame" with John Lennon which became his first American No. 1 single in 1975. An accomplished actor, Bowie starred in The Man Who Fell to Earth in 1976. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996. Bowie died on January 10, 2016, from cancer at the age of 69.

Early Years

Known as a musical chameleon for his ever-changing appearance and sound, David Bowie was born David Robert Jones in Brixton, South London, England, on January 8, 1947.

David showed an interest in music from an early age and began playing the saxophone at age 13. He was greatly influenced by his half-brother Terry, who was nine years older and exposed young David to the worlds of rock music and beat literature.

But Terry had his demons, and his mental illness, which forced the family to commit him to an institution, haunted David for a good deal of his life. Terry committed suicide in 1985, a tragedy that became the focal point of Bowie's later song, "Jump They Say."

After graduating from Bromley Technical High School at 16, David started working as a commercial artist. He also continued to play music, hooking up with a number of bands and leading a group himself called Davy Jones and the Lower Third. Several singles came out of this period, but nothing that gave the young performer the kind of commercial traction he needed.

Out of fear of being confused with Davy Jones of The Monkees, David changed his last name to Bowie, a name that was inspired by the knife developed by the 19th century American pioneer Jim Bowie.

Eventually, Bowie went out on his own. But after recording an unsuccessful solo album, Bowie exited the music world for a temporary period. Like so much of his later life, these few years proved to be incredibly experimental for the young artist. For several weeks in 1967 he lived at a Buddhist monastery in Scotland. Bowie later started his own mime troupe called Feathers.

Around this time he also met the American-born Angela Barnett. The two married on March 20, 1970, and had one son together, whom they nicknamed "Zowie," in 1971, before divorcing in 1980. He is now known by his birth name Duncan Jones.

Pop Star

By early 1969, Bowie had returned full time to music. He signed a deal with Mercury Records and that summer released the single "Space Oddity." Bowie later said the song came to him after seeing Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. "I went stoned out of my mind to see the movie and it really freaked me out, especially the trip passage."

The song quickly resonated with the public, sparked in large part by the BBC's use of the single during its coverage of the Apollo 11 moon landing. The song enjoyed later success in the United States, when it was released in 1972 and climbed to number 15 on the charts.

Bowie's next album, The Man Who Sold the World (1970), further catapulted him to stardom. The record offered up a heavier rock sound than anything Bowie had done before and included the song "All the Madmen," about his institutionalized brother, Terry. His next work, 1971's Hunky Dory, featured two hits: the title track that was a tribute to Andy Warhol, the Velvet Underground and Bob Dylan; and "Changes," which came to embody Bowie himself.

Meet Ziggy Stardust

As Bowie's celebrity profile increased, so did his desire to keep fans and critics guessing. He claimed he was gay and then introduced the pop world to Ziggy Stardust, Bowie's imagining of a doomed rock star, and his backing group, The Spiders from Mars.

His 1972 album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, made him a superstar. Dressed in wild costumes that spoke of some kind of wild future, Bowie, portraying Stardust himself, signaled a new age in rock music, one that seemed to officially announce the end of the 1960s and the Woodstock era.

More Changes

But just as quickly as Bowie transformed himself into Stardust, he changed again. He leveraged his celebrity and produced albums for Lou Reed andIggy Pop. In 1973, he disbanded the Spiders and shelved his Stardust persona. Bowie continued on in a similar glam rock style with the albumAladdin Sane (1973), which featured "The Jean Genie" and "Let's Spend the Night Together," his collaboration with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards.

Around this time he showed his affection for his early days in the English mod scene and released Pin Ups, an album filled with cover songs originally recorded by a host of popular bands, including Pretty Things and Pink Floyd.

By the mid 1970s Bowie had undergone a full-scale makeover. Gone were the outrageous costumes and garish sets. In two short years he released the albums David Live (1974) and Young Americans (1975). The latter album featured backing vocals by a young Luther Vandross and included the song "Fame," co-written with John Lennon, which became Bowie’s first American number one single.

In 1980 Bowie, now living in New York, released Scary Monsters, a much-lauded album that featured the single "Ashes to Ashes," a sort of updated version of his earlier "Space Oddity."

Three years later Bowie recorded Let's Dance (1983), an album that contained a bevy of hits such as the title track, "Modern Love" and "China Girl," and featured the guitar work of Stevie Ray Vaughan.

Of course, Bowie's interests didn't just reside with music. His love of film helped land him the title role in The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976). In 1980, Bowie performed on Broadway in The Elephant Man.

Over the next decade, Bowie bounced back and forth between acting and music, with the latter especially suffering. Outside of a couple of modest hits, Bowie's musical career languished. His side project with musicians Reeve Gabrels and Tony and Hunt Sales known as Tin Machine released two albums Tin Machine (1989) and Tin Machine II (1991), which both proved to be flops. His much-hyped album Black Tie White Noise (1993), which Bowie described as a wedding gift to his new wife, supermodel Iman, also struggled to resonate with record buyers.

Oddly enough, the most popular Bowie creation of late has been Bowie Bonds, financial securities the artist himself backed with royalties from his pre-1990 work. Bowie issued the bonds in 1997 and earned $55 million from the sale. The rights to his back catalog were returned to him when the bonds matured in 2007.

|

| dThe rise of David Bowie by Mick Rock |

Recent Years

In 2004 Bowie received a major health scare when he suffered a heart attack while onstage in Germany. He made a full recovery and went on to work with bands such as Arcade Fire and with the actress Scarlett Johansson on her album Anywhere I Lay My Head (2008), a collection of Tom Waits covers.

Bowie, who was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996, was a 2006 recipient of the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. He kept a low profile for several years until the release of his 2013 album The Next Day, which skyrocketed to number 2 on the Billboard charts. The following year, Bowie released a greatest hits collection Nothing Has Changed, which featured a new song "Sue (Or in a Season of Crime)."

In 2015, he collaborated on Lazarus, an Off-Broadway rock musical starring Michael C. Hall, which revisited his character from The Man Who Fell to Earth.

He released Blackstar, his final album on January 8, 2016, his birthday. New York Times critic Jon Pareles noted that it was a "strange, daring and ultimately rewarding" work "with a mood darkened by bitter awareness of mortality." Only a few days later, the world would learn that the record had been made under difficult circumstances.

|

| David Bowie Photo by Mark Rock |

Death

The music icon died on January 10, 2016, two days after his 69th birthday. A post on his Facebook page read: “David Bowie died peacefully today surrounded by his family after a courageous 18 month battle with cancer."

He was survived by his wife Iman, his son Duncan Jones and daughter Alexandria. Bowie also left behind an impressive musical legacy, which included 26 albums. His producer and friend Tony Visconti wrote on Facebook that his last record, Blackstar, was "his parting gift."

Friends and fans were heartbroken at his passing. Iggy Pop wrote on Twitter that "David's friendship was the light of my life. I never met such a brilliant person." The Rolling Stones remembered him on Twitter as "a wonderful and kind man" and "a true original." And even those who didn't know personally felt the impact of his work. Kanye West tweeted, "David Bowie was one of my most important inspirations." Madonna posted "This great Artist changed my life!"

David Bowie obituary

U

ntil the last, David Bowie, who has died of cancer, was still capable of springing surprises. His latest album, Blackstar, appeared on his 69th birthday on 8 January, and showed that his gift for making dramatic statements as well as challenging, disturbing music had not deserted him.

Throughout the 1970s, Bowie was a trailblazer of musical trends and pop fashion. Having been a late-60s mime and cabaret entertainer, he evolved into a singer-songwriter, and a pioneer of glam-rock, then veered into what he called “plastic soul”, before moving to Berlin to create innovative electronic music.

In subsequent decades his influence became less pervasive, but he remained creatively restless and constantly innovative across a variety of media. His capacity for mixing brilliant changes of sound and image underpinned by a genuine intellectual curiosity is rivalled by few in pop history. Blackstar was proof that this curiosity had not diminished in his later career.

Bowie was born David Robert Jones in Brixton, south London. His mother, Peggy, had met his father, John, after he was demobilised from second world war service in the Royal Fusiliers. John subsequently worked for the Barnardo’s children’s charity. They married in September 1947, eight months after David’s birth, when John’s divorce from his first wife, Hilda, became absolute.

In 1953 the family moved to Bromley, Kent, where David attended Burnt Ash junior school and showed aptitude in singing and playing the recorder. Later, after he failed his 11-plus exam, he went to Bromley technical high school and studied art, music and design. His half-brother, Terry Burns, nearly a decade older than David, introduced him to jazz musicians, such as John Coltrane andMiles Davis, and in 1961 David’s mother bought him a plastic saxophone, introducing him to an instrument that would become a recurring ingredient in his music.

After a 1962 schoolyard punch-up, the pupil in David’s left eye remained permanently dilated, having the serendipitous effect of lending him a vaguely unearthly appearance (the thrower of the punch, George Underwood, remained a close friend and later designed Bowie’s album artwork).

At 15, David formed his first band, the Kon-rads, a primitive rock’n’roll combo that contained a fluctuating number of members, including Underwood. He quickly became disillusioned with his band’s lack of ambition and quit to form a new outfit, the blues-influenced King Bees. They released a single called Liza Jane, but when it disappeared without trace, David jumped ship again and joined the Manish Boys. Named after a Muddy Waters track, they too were blues-orientated. Their single I Pity the Fool proved no more chart-friendly than Liza Jane had done, after which the restless Davy Jones was on the move once more.

His next port of call was the Lower Third, an R&B band from Margate, Kent. The group thought they were auditioning for a singer and equal member, but once they had hired David, they were taken aback when he issued a press statement saying: “This is to inform you of the existence of Davie [sic] Jones and the Lower Third.” Moreover, David, abetted by his new manager Ralph Horton, a former tour manager for the Moody Blues, decreed that the band should be decked out in fashionable mod attire, in emulation of the Who. Fellow members of the Lower Third could not help noticing David’s flamboyant, even effeminate performing style. They released a Jones-penned single, the aptly named You’ve Got a Habit of Leaving, but despite receiving a handful of radio plays, it failed to chart.

It was clear that David’s talents and ambition dictated that he should go solo, and Horton provoked a split with the Lower Third by announcing that there was not enough money to pay their fees. David now adopted the name Bowie to avoid confusion with Davy Jones of the Monkees, and put together a new group via an advertisement in Melody Maker, specifying that he wanted musicians “to accompany a singer”. The new band was named the Buzz.

He dropped Horton after a botched music publishing deal, and in his place hired Ken Pitt, a far more substantial figure who had had success with Mel Tormé and Manfred Mann. Pitt secured an album deal for Bowie with Decca’s Deram label, which resulted in an LP entitled simply David Bowie, released in June 1967. It was preceded by the novelty single The Laughing Gnome, a flop at the time but a top 10 hit when reissued in 1973. Bowie later said of his debut album: “I didn’t know if I was Max Miller or Elvis Presley.” But within its disjointed mix of styles, it found Bowie reflecting on issues such as childhood, sexual ambiguity and the nature of stardom. By the time the album was released, Bowie had already got rid of the Buzz, again citing lack of money.

For a time he studied theatre and mime with the dancer Lindsay Kemp, and in 1969 he started a folk club at the Three Tuns pub in Beckenham, Kent. This developed into the Beckenham Arts Lab, and a variety of future stars, includingPeter Frampton, Steve Harley, Rick Wakeman and Bowie’s future producer Tony Visconti, performed there.

In July 1969 Bowie released Space Oddity, the song that would give him his initial commercial breakthrough. Timed to coincide with the Apollo 11 moon landing, it was a top five UK hit. The accompanying album was originally called Man of Words / Man of Music, but was later reissued as Space Oddity.

The following year was a momentous one for Bowie. His brother Terry was committed to a psychiatric institution (and would kill himself in 1985), and his father died. In March, Bowie married Angela Barnett, an art student. He dumped Pitt and recruited the driven and aggressive Tony DeFries, prompting Pitt to sue successfully for compensation.

Artistically, Bowie was powering ahead. The Man Who Sold the World was released in the US in late 1970 and in the UK the following year under Bowie’s new deal with RCA Victor, and with its daring songwriting and broody, hard-rock sound, it was the first album to do full justice to his writing and performing gifts. The title track remains one of his most atmospheric compositions, and songs such as All the Madmen and The Width of a Circle were formidably inventive and accomplished. The album’s themes included immortality, insanity, murder and mysticism, evidence that Bowie was a songwriter who was thinking way beyond pop’s usual boundaries.

The Man Who Sold the World was significant in other ways too. Its producer, Visconti, became a long-term ally, and in the guitarist Mick Ronson and the drummer Woody Woodmansey, Bowie had found the core of what would become the Spiders from Mars. The UK cover pictured Bowie lounging in a long dress and bearing a striking resemblance to Lauren Bacall, playing on the theme of sexual ambiguity that he would exploit so successfully.

He followed it with Hunky Dory (1972), a mix of wordy, elaborate songwriting (The Bewlay Brothers or Quicksand), crunchy rockers (Queen Bitch) and infectious pop songs (Kooks). It was an excellent collection that met with only moderate success, but that all changed with The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars later that year.

This time, Bowie emerged as a fully fledged science-fiction character – an intergalactic glam-rock star visiting a doomed planet Earth – and the album effectively wrote the script for his own stardom. The hit single Starman brought instant success for the album, while Bowie’s ravishing stage costumes and sexually provocative performances (following his carefully timed claim in a Melody Maker interview that he was gay) triggered fan enthusiasm unseen since Beatlemania. Seeing Bowie perform as Ziggy on Top of the Pops was a life-changing experience for a generation of pop listeners in glum 70s Britain.

Everything Bowie touched turned to gold, such as his song All the Young Dudeswhich provided a career-reviving hit for Mott the Hoople, or Lou Reed’s album Transformer, which he co-produced with Ronson. He scored his first UK No 1 album with Aladdin Sane (1973), which generated the hit singles The Jean Genieand Drive-in Saturday. But Bowie was already planning fresh career moves, and in July 1973 he shocked his audience at the Hammersmith Odeon by announcing the retirement of Ziggy Stardust.

He made Pin Ups, a transitional album of cover versions, before embarking on the sinister concept album Diamond Dogs, intended as a musical version of George Orwell’s 1984. Bowie’s commercial instincts remained in fine working order, however, and the album brought further hit singles with the title track and Rebel Rebel.

He took his new music to the US in 1974 with the elaborately theatrical Diamond Dogs tour, which was filmed by the BBC’s Alan Yentob for the documentary Cracked Actor. However, professional pressures and an escalating cocaine habit were making Bowie paranoid and physically emaciated.

His increasing interest in funk and soul music came to the fore on the deliciously listenable Young Americans (1975), which gave him a US chart-topper with Fame (featuring John Lennon as a guest vocalist) and earned him a slot on the American TV show Soul Train. This was Bowie’s so-called “plastic soul” album, which he described as “the squashed remains of ethnic music as it survives in the age of Muzak, written and sung by a white limey”.

But once again, Bowie’s frantic creativity was accompanied by crises in his business life. He fired Defries, which spurred long and tortuous litigation and cost Bowie millions, then hired his lawyer, Michael Lippman, as his manager. A year later he went through the sacking-and-lawsuit process all over again with Lippman.

Yet he was still breaking new musical ground. Station to Station (1976), a euphoric dose of what might be called synthetic art-funk, introduced a new persona, the Thin White Duke, which Bowie had carried over from his headlining performance as Thomas Jerome Newton, the melancholy space traveller, in Nicolas Roeg’s film The Man Who Fell to Earth.

But Bowie’s own connection to terra firma was looking increasingly shaky. He told Rolling Stone magazine about his admiration for fascism, and provoked outrage when his wave to the crowd while arriving in an open-topped Mercedes at Victoria station in London was interpreted as Nazi salute.

He found some breathing space by buying a home in Switzerland, where he rediscovered his interest in art and drawing, but by the end of 1976 he had taken up residence in Berlin, where he was accompanied by Iggy Pop – with whom he was working on Iggy’s album, The Idiot – and Brian Eno, who would be the catalyst for another of Bowie’s musical leaps forward.

The upshot was the so-called “triptych” of Low, Heroes (both 1977) and Lodger (1979), where Bowie mixed Krautrock influences with Eno-driven synthesizer mood-music, with at least some pop accessibility for good measure (such as Low’s Sound and Vision or Lodger’s Boys Keep Swinging). Lodger, though recorded in Montreux and New York, used the same personnel as the previous two, with Eno once again acting as creative ringmaster. Meanwhile, Bowie found time to film another leading movie role, appearing as Count Paul von Przygodski in Just a Gigolo (1978).

Bowie’s relationship with his wife had been disintegrating under the pressures of success and the couple’s hedonistic, promiscuous lifestyle, and they would divorce in 1980. This was a year of further creative triumph, bringing a fine album, Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) and its spin-off chart-topping single, Ashes to Ashes, followed by Bowie’s well-received stint as John Merrick in The Elephant Man on the Broadway stage. To make the accompanying video for Ashes to Ashes, he went to the Blitz club in London and recruited several leading lights from the New Romantic movement, a collection of bands including Visage and Spandau Ballet, who owed much of their inspiration to Bowie.

With hindsight, Ashes to Ashes can be seen as the point where Bowie’s cutting edge began to lose its sharpness, and he was never again quite the cultural pathfinder he had been in his heyday. This process expressed itself in the way he restlessly bounced between collaborators.

He bagged a No 1 single with his 1981 partnership with Queen, Under Pressure, while becoming increasingly involved in crossovers between different media. He appeared in the German movie Christiane F (1981) and wrote music for the soundtrack, and his lead role in the BBC’s production of Bertolt Brecht’s Baal (1982) was accompanied by his five-track EP of songs from the play. He registered another chart hit with Cat People (Putting Out Fire) from Paul Schrader’s movie Cat People (1982).

Bowie continued to make progress as a screen actor with appearances in The Hunger (alongside Catherine Deneuve) and the second world war drama Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence, both released in 1983. Musically, this was the year in which he marshalled his forces for an all-out commercial onslaught with the album Let’s Dance and follow-up concerts. With co-production from Chic’s Nile Rodgers, Let’s Dance moulded Bowie into a crowd-friendly global rock star, with the album and its singles Let’s Dance, China Girl and Modern Love all becoming huge international hits.

This was the heyday of MTV, and Bowie’s knack for eye-catching videos fuelled this commercial splurge, while the six-month Serious Moonlight tour drew massive crowds. It was to be the most commercially successful period of his career.

Tonight (1984) could not repeat the trick, though it delivered the hit Blue Jean, whose short accompanying film Jazzin’ for Blue Jean earned Bowie a Grammy. But his profile gained another boost from his appearance at the 1985 Live Aid famine relief concert at Wembley stadium, where he was one of the standout performers. In addition, he teamed up with Mick Jagger to record the fundraising single Dancing in the Street, which sped to No 1.

Bowie then returned to the multimedia trail with an appearance in Julien Temple’s shambolic film Absolute Beginners (1986), from which he salvaged some personal kudos by supplying the winsome title song. He also wrote five songs for Jim Henson’s fantasy film Labyrinth, as well as taking the role of Jareth the Goblin King.

In 1987, a solo album, Never Let Me Down, performed reasonably well commercially, but poor reviews were endorsed by Bowie himself (he described it as “an awful album”). The follow-up Glass Spider tour was castigated for its soulless over-production.

After playing Pontius Pilate in Martin Scorsese’s film The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), Bowie’s next move was the heavy-rock band Tin Machine, with which he sought to appear as a band member rather than as a solo star. Their album Tin Machine (1989) and tour earned a mixture of modest acclaim and howls of outrage. However, by the time they released a second album, Bowie had abandoned the pretence of being “one of the boys” by undertaking 1990’s greatest hits tour Sound + Vision, unashamedly designed to promote the reissue of his back catalogue. Tin Machine dissolved in 1992.

A few days after his appearance at the Freddie Mercury tribute concert at Wembley stadium in April 1992, Bowie married the Somalian model Iman, whom he had met 18 months earlier, and the couple bought a home in New York. This new start in his private life coincided with a search for fresh musical inspiration.

For the album Black Tie White Noise (1993), he reunited with Rodgers and sprinkled elements of soul, electronica and hiphop into the mix. It topped the UK album chart and yielded a top 10 single, Jump They Say.

However, Bowie’s quest for new sounds to plunder began to evince an air of desperation. Outside (1995) found him reunited with Eno and was another commercial success, despite its laborious concept and clumsy adoption of grungy, industrial sounds, while Earthling (1997) borrowed elements of the drum’n’bass style practised by such UK artists as Goldie and Asian Dub Foundation. One of the album tracks was I’m Afraid of Americans, originally written for the movie Showgirls but remade under the auspices of Trent Reznor from Nine Inch Nails. Released as a single, it sat on the US Billboard Hot 100 for four months.

Bowie was demonstrating unexpected forms of creativity in other areas. In 1997 he made history of a sort by launching his Bowie bonds, whereby he netted $55m upfront by surrendering his royalties over the bonds’ 10-year term. In 2000, he delved into online banking with BowieBanc, giving customers an international banking service as well as cheques and debit cards with his picture on them.

New media and technology influenced his recordings too. His 1999 album Hours… was based around music he had written for a computer game called Omikron, in which Bowie and Iman appeared as characters. Some listeners detected a return to the Hunky Dory days in the album’s reflective, self-analytical musings, though the songs could not match those former glories.

As an adopted New Yorker, Bowie was the opening act at the Concert for New York City in October 2001, where he joined Paul McCartney, Jon Bon Jovi, Billy Joel, the Who and Elton John in a benefit show six weeks after the 9/11 attacks. Bowie sang Paul Simon’s song America and his own Heroes.

He played himself in Ben Stiller’s fashion industry spoof Zoolander (2001). The following year, he was artistic director of the Meltdown festival on the South Bank in London, opening the event by performing the first concert of his own Heathen tour, in support of his album of the same name. The work reunited Bowie with Visconti for the first time since Scary Monsters, and sold 2m copies worldwide. It was nominated for the annual Mercury prize.

|

| David Bowie, 1993 Photo by Mick Rock |

A re-energised Bowie was back in the studio with Visconti the following year for Reality, another successful outing welcomed for its energy and musical freshness. However, in the midst of his Reality tour in 2004, Bowie was stricken with chest pains while performing at the Hurricane festival in Germany and underwent an emergency angioplasty procedure in Hamburg to clear a blocked artery.

He took the medical emergency as a warning and reduced the pace of his activities. He made a handful of guest appearances, including a couple of live shows with the Canadian band Arcade Fire, then in 2006 announced he would be taking a year off from touring and recording.

Despite this, shortly afterwards he appeared with Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour at the Royal Albert Hall, singing the Floyd classics Arnold Layne and Comfortably Numb. In February that year he was given a Grammy lifetime achievement award, having been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996. In The Prestige (2006), Christopher Nolan’s film about two battling magicians, Bowie featured as the inventor Nikola Tesla. Nolan said he cast Bowie because he wanted somebody “extraordinarily charismatic”.

In 2007 Bowie was curator of the eclectic High Line festival in New York, and included among his choices Arcade Fire, Laurie Anderson and the comedian Ricky Gervais. In 2008 he contributed vocals to a couple of tracks on Scarlett Johansson’s album of Tom Waits cover versions, Anywhere I Lay My Head.

In 2010, a live double CD, A Reality Tour, was released on Bowie’s own ISO Records. Recorded in Dublin in 2003, it was a survey of most of the key moments in his musical career. Reviewers were enthusiastic, but could not help noticing the valedictory feel of the album. “Nobody really knows if Bowie is hanging up the spacesuit for good,” said Rolling Stone. “But if so, this is one hell of an exit.”

But there was more to come. In 2011 he released the album Toy, which dated back to 2001 and comprised tracks from Heathen and their B sides plus versions of older material. Of far greater significance was The Next Day (2013), his first album of new material in a decade. Produced by Visconti, it was preceded by the single Where Are We Now?, which gave him his first UK top 10 hit since 1993. The album topped charts in Britain and around the world, reaching No 2 in the US. In 2014 Bowie was given the Brit Award for Best British Male, making him the oldest recipient in the awards’ history.

He is survived by Iman, their daughter, Lexi, his stepdaughter, Zulekha, and his son, Duncan (formerly known as Zowie, then Joe), from his first marriage.

• David Bowie (David Robert Jones), singer, songwriter and actor, born 8 January 1947; died 10 January 2016

|

| Street scene: David Bowie outside the Carlyle hotel in New York in the early 80s. Photograph: Art Zelin/Getty Images |

David Bowie's last days: an 18-month burst of creativity

Over the last months of his life, the singer was able to shake off late career doldrums and, despite his illness, find a final creative surge

Joanna Walters and Edward Helmore in New York

Saturday 16 January 2016 12.39 GMT

F

or more than a decade before his death David Bowie seemed to disappear. Beset by ill health after an on-stage heart attack in 2004, he largely withdrew into a life at home in New York, becoming a ghost in the city where he had lived for a quarter of a century.

Yet as the world comes to terms with his death this week, admirers are digesting a remarkable late burst of creativity, a dramatic 18-month flourish capped by an apparently exquisitely well-crafted exit.

At 69, Bowie reasserted himself both as a musician – Blackstar, the album released two days before his death, is topping charts around the world – and as a questing creative figure whose vision is still playing out on the New York theatre stage.

How did Bowie pull this off from the penthouse duplex he shared with wife, Iman, and 15-year-old daughter, Lexi, in the Nolita section of downtown Manhattan?

The singer’s encroaching frailty meant he kept his life local. The theatre where his play Lazarus is running is no more than a few minutes walk away; Magic Shop, the studio where he recorded albums Blackstar and The Next Day, is even closer, on Crosby Street.

Each place would offer Bowie a last opportunity to work in the musical and theatrical worlds that he had specialised in amalgamating throughout his career. “He wasn’t any single thing,” longtime collaborator Mick Rock told the Guardian. “He was the great synthesizer.”

The picture that has emerged over the past few days is of a man who was able to shake off late career doldrums and, in spite of declining health, find a final, focused burst of creativity.

First, in 2013, came The Next Day, an album that was a stylistic tour of his career; then the V&A’s David Bowie Is – an exhibit of 300 objects of Bowie memorabilia revealing the consideration with which he had preserved the artefacts of his career; the play Lazarus, now set for London’s West End; and finally Blackstar, a jazz record that launched with a video that appears to anticipate his death.

According to Bowie’s longtime producer Tony Visconti, Bowie had known since at least November that his cancer was terminal. But even in his final weeks, Bowie had no idea how little time was left and was talking about a Blackstar follow-up.

Pictures from the opening night of Lazarus on 7 December last year showed Bowie still handsome and immaculate but possibly showing signs that he may have been unwell. Theatre producer Robert Fox, who worked with him on Lazarus, said Bowie never complained.

“The work was great and working with him was wonderful but it wasn’t great that he wasn’t well. It was not good at all. Some days he just wasn’t able to be around, but whenever he could be, it [his cancer] didn’t interfere with his contribution. It was just horrible for him, rather than difficult for us.”

Fox believed the work was not specifically coloured by Bowie’s sense of his own mortality. “The struggle with mortality goes on whether or not you’re unwell. People write about that stuff even when they’re in perfectly good health,” he said. But Fox, who helped Bowie find a director and cast the actors, concedes it must have had some effect.

“He would talk about his illness only to the extent that it affected his work. Not in any other way. He never grumbled. But I don’t think he planned on not being around. He was optimistic that something (a treatment) would come along that meant that he could be.”

Bowie had been battling cancer for six months when he entered Magic Shop’s expansive studio facilities in January 2015 to record his 25th album. The studio, which has also been used by Coldplay and Arcade Fire, was already known to him; he had recorded much of his previous album The Next Day there. But instead of rock musicians, he brought seven demos to progressive jazz saxophonist Donny McCaslin.

The sessions were short and light-hearted, typically running from 11am to 4pm over three sessions of a week through to March. James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem came in to add synths and percussion and the tracks were finished off in Visconti’s own studio in April.

Visconti, who produced the album over the first few months of 2015, told Rolling Stone that Bowie showed up for some Blackstar sessions without eyebrows or hair after undergoing chemotherapy.

“There was no way he could keep it a secret from the band,” he told the magazine. “But he told me privately and I really got choked up when we sat face to face talking about it.”

Bowie’s affliction had not dulled his enthusiasm for work. “His energy was that of a very young person diving into everything with fearless joy and abandon,” said recent Bowie collaborator Maria Schneider, the orchestral-jazz composer. “Not to say he wasn’t serious. He was very clear about what he did and didn’t like.”

Annie-B Parson, of New York’s Big Dance Theater company, was the choreographer on the Lazarus musical and worked in close proximity with Bowie from September until the opening night in December.

She said she did not know he was ill and did not think the actors knew either as they worked quickly to develop the show in a tiny studio at the New York Theater Workshop.

But the director of the musical, Ivo van Hove, told her something that she only now realises the significance of. “At the beginning, he said this was the saddest piece he had ever worked on,” she said. “It’s deeply connected to death and a person contemplating his own existence from the first moment we see him.”

During rehearsals, Bowie sat quietly, elegantly dressed in grey sweater and white shirt, writing with a stub of pencil on a piece of paper. Physically, “all criss-crossed”, the choreographer noted, his slender arms and legs twisted about each other in concentration. Bowie would not intervene, but the creative team would get feedback.

“He insisted on spectacle. What struck me was that Bowie was from some other place, he wasn’t of this planet and he was cool with that,” Parson said.

It only occurred to her with hindsight that a person’s knowledge that they may have limited time left might fuel their creativity. Bowie was suddenly prolific, driven. “There was almost an insistence that he had so much to say. He needed to get out these songs in time. And he did,” she said.

Speaking on Friday from Warsaw, van Hove said: “The first thing that struck me when I met in a room in New York with David and Enda [Walsh, Bowie’s co-writer on the piece] and they read it to me and played some of the music was the existential theme – life and death and is there life after death or can you go on living just in your mind or your imagination?”

When Bowie told van Hove, in strictest confidence, in November 2014, that he had cancer and might not survive the project, the songs he was writing became deeper, especially Lazarus, the song of the eponymous musical and single.

“It is like his testament,” said van Hove.

Bowie’s creative surge was stunning. When he was feeling ill after treatment, he would stay away from rehearsals, but was intimately involved when in attendance and a genuine collaborator who thrived off his cohorts’ ideas, van Hove said.

“He was private about the details of his health situation. I didn’t question him, but I knew he did not want to die. He was in a struggle for life during those 18 months,” he said.

Some of the songs in the musical convey huge inner rage and a protest about violence in society, overlaid with poetry and layers of sound. “But in person he was always the perfect gentleman,” van Hove said. As Bowie became sicker, later in 2015, van Hove said he saw fear in his eyes. “He was fragile,” he said.

After the opening night of Lazarus, Bowie had to sit down backstage with van Hove and Iman, exhausted after taking his bow. “I escorted him to his car and I somehow knew it was the last time I would see him.”

Music video director Johan Renck was already thrilled to be working with his childhood hero last July on the title track of the diamond heist TV drama The Last Panthers that he had directed in England, when the British pop icon told him there was more to the tune they had just recorded. A lot more – a version that turned out to be Blackstar, the towering single from the album Bowie had been writing.

“I flew from London to New York and met with him at his office in Soho to listen to the full track. He put his hand on my shoulder and said with a grin – ‘I must warn you, it’s 10 minutes long’. There was no way I could say no. He had this warmth and this infectious smile and I knew it would be an interesting journey,” Renck said.

The two began a fiercely intense and, as it turned out, all too short collaboration.

“Over Skype he said ‘I feel I have to tell you this. I’m very ill and I may not make it’. I had been in this playful mood, pitching ideas back and forth with him like giddy 12-year-olds and I was absolutely shocked. He said: ‘I don’t even know if by the time we shoot this video you will have to have a replacement for me to perform in it’,” Renck said.

Bowie gave Renck no details of his cancer, only that he would be in cycles of treatment that meant he would have “my good periods and bad periods”, the director said. Bowie asked Renck not to tell a soul – this is the first time he has spoken publicly since Bowie’s death.

When Bowie and Renck came to shoot the video for Blackstar in September and, in November, the next single Lazarus, the mood was exuberant.

They shot Bowie performing for one day for each video and just five hours on those days in a studio in Brooklyn. That was all his health would take, Renck said.

Bowie wanted it to feature an isolated village, then Renck came up with the idea of rituals that mixed the occult with a celebration of life. Bowie also wanted a scarecrow in the video, Renck said, and sent Renck his sketch for the macabre character Button Eyes that he plays in both videos. The sketch showed a bandaged head, buttons for eyes and just a small strip of a Mohawk for hair.

“Bowie didn’t know if he would have hair left by the time of the shoot,” said Renck.

In fact he did, a splendid shock of silvery grey hair – though he had to be careful or it came out in tufts because of his cancer treatment.

Unlike the sweeping anthem Blackstar, Renck described Lazarus as a little gem. Bowie reappears as Button Eyes, tormented on a hospital bed.

“I just thought of it as the Biblical tale of Lazarus rising from the bed. In hindsight, he obviously saw it as the tale of a person in his last nights,” said Renck.

While working, Bowie talked of his family but kept himself quite private, while being very easygoing and friendly with the small crew that worked on the intimate shoot.

He would arrive so suave in suit and fedora and sip cups of tea, Renck said, Despite the warning, he did not realise the star was so gravely ill because he seemed so spritely while shooting. He would get tired and take breaks, Renck said, but he seemed so happy.

The video of Lazarus shows Button Eyes and also Bowie’s other “character”, a dancer in a slick suit, gyrating in classic Bowie camp style then writing frenetically, a man desperately running out of time. Finally the figure retreats into a wardrobe and shuts the doors behind him.

It’s haunting but also witty, mocking death, Renck said.

“So British, the wit, like a guilt thing, making sure it’s not coming across as too serious or pretentious – and yet that enhances the humanity of it.”

Renck and Bowie also agreed that the joke was that the star, legendary for his gender-bending and fluid sexuality, was going “back into the closet”.

“The closet, or coffin, if you will,” said Renck.

1967: David Bowie

1969: Space Oddity

1970: The Man Who Sold the World

1971: Hunky Dory

1972: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars

1973: Aladdin Sane

1973: Pin Ups

1974: Diamond Dogs

1975: Young Americans

1976: Station to Station

1977: Low

1977: "Heroes"

1979: Lodger

1980: Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)

1983: Let's Dance

1984: Tonight

1987: Never Let Me Down

1993: Black Tie White Noise

1995: Outside

1997: Earthling

1999: Hours...

2002: Heathen

2003: Reality

2013: The Next Day

2016: Blackstar

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario