|

| George Bellows |

George Wesley Bellows / Original Lithographs & Drawings

From the city to the sea / The life and art of George Bellows

George Bellows / A Shot Through the Art

George Wesley Bellows (August 12 or August 19,1882 – January 8, 1925) was an American realist painter, known for his bold depictions of urban life in New York City. He became, according to the Columbus Museum of Art, "the most acclaimed American artist of his generation".

|

| Nude With a Parrot, 1915 George Bellows |

Youth

George Wesley Bellows was born and raised in Columbus, Ohio. He was the only child of George Bellows and Anna Wilhelmina Smith Bellows (he had a half-sister, Laura, 18 years his senior). He was born four years after his parents married, at the ages of fifty (George) and forty (Anna). His mother was the daughter of a whaling captain based in Sag Harbor, Long Island, and his family returned there for their summer vacations. He began drawing well before kindergarten, and his elementary–school teachers often asked him to decorate their classroom blackboards at Thanksgiving and Christmas.

At age 10, George took to athletics, and trained to be a baseball and basketball player. He became good enough at both sports to play semipro ball for years afterward. During his senior year, a baseball scout from the Indianapolis team made him an offer. He declined, opting to enroll at The Ohio State University (1901–1904). There he played for the baseball and basketball teams, and provided illustrations for the Makio, the school's student yearbook. He was encouraged to become a professional baseball player, and he worked as a commercial illustrator while a student and continued to accept magazine assignments throughout his life. Despite these opportunities in athletics and commercial art, Bellows desired success as a painter, although his parents didn't encourage it. He left Ohio State in 1904, just before he was to graduate, and moved to New York City to study art.

Bellows was soon a student of Robert Henri, who at the time was teaching at the New York School of Art. While studying there, Bellows became associated with Henri's "The Eight" and the Ashcan School, a group of artists who advocated painting contemporary American society in all its forms. By 1906, Bellows and fellow art student Edward Keefe had set up a studio at 1947 Broadway.

|

| New York, 1911 George Bellows |

New York

Bellows first achieved widespread notice in 1908, when he and other pupils of Henri organized an exhibition of mostly urban studies. While many critics considered these to be crudely painted, others found them welcomely audacious, a step beyond the work of his teacher. Bellows taught at the Art Students League of New York in 1909, although he was more interested in pursuing a career as a painter. His fame grew as he contributed to other nationally recognized juried shows.

Bellows' urban New York scenes depicted the crudity and chaos of working-class people and neighborhoods, and satirized the upper classes. From 1907 through 1915, he executed a series of paintings depicting New York City under snowfall. In these paintings Bellows developed his strong sense of light and visual texture, exhibiting a stark contrast between the blue and white expanses of snow and the rough and grimy surfaces of city structures, and creating an aesthetically ironic image of the equally rough and grimy men struggling to clear away the nuisance of the pure snow. However, Bellows' series of paintings portraying amateur boxing matches were arguably his signature contribution to art history. They are characterized by dark atmospheres, through which the bright, roughly lain brushstrokes of the human figures vividly strike with a strong sense of motion and direction.

Social and political themes

Growing prestige as a painter brought changes in his life and work. Though he continued his earlier themes, Bellows also began to receive portrait commissions, as well as social invitations, from New York's wealthy elite. Additionally, he followed Henri's lead and began to summer in Maine, painting seascapes on Monhegan and Matinicus islands.

At the same time, the always socially conscious Bellows also associated with a group of radical artists and activists called "the Lyrical Left", who tended towards anarchism in their extreme advocacy of individual rights. He taught at the first Modern School in New York City (as did his mentor, Henri), and served on the editorial board of the socialist journal The Masses, to which he contributed many drawings and prints beginning in 1911. However, he was often at odds with other contributors due to his belief that artistic freedom should trump any ideological editorial policy. Bellows also dissented from this circle in his very public support of U.S. intervention in World War I. In 1918, he created a series of lithographs and paintings that graphically depicted atrocities which the Allies said had been committed by Germany during its invasion of Belgium. Notable among these was The Germans Arrive, which gruesomely illustrated a German soldier restraining a Belgian teen whose hands had just been severed. However, his work was also highly critical of the domestic censorship and persecution of antiwar dissenters conducted by the U.S. government under the Espionage Act.

He was also criticized for some of the liberties he took in capturing scenes of war. The artist Joseph Pennell argued that because Bellows had not witnessed the events he painted firsthand, he had no right to paint them. Bellows responded that he had not been aware that Leonardo da Vinci "had a ticket to paint the Last Supper".

Later life

As Bellows' later oils focused more on domestic life, with his wife and daughters as beloved subjects, the paintings also displayed an increasingly programmatic and theoretical approach to color and design, a marked departure from the fluid muscularity of the early work.

One of Bellows' central subjects was the sea, and he painted over 250 scenes of it during the course of his career. The Fisherman (1917), a significant late canvas focusing on the topic that he made while visiting Carmel, California, is in the collection of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

In addition to painting, Bellows made significant contributions to lithography, helping to expand the use of the medium as a fine art in the U.S. He installed a lithography press in his studio in 1916, and between 1921 and 1924 he collaborated with master printer Bolton Brown on more than a hundred images. The Amon Carter Museum of American Art holds one of the largest collections of Bellows' lithographs, a set of 220 prints acquired from the artist's estate in 1985.There are also large collections of his lithographs at the Boston Public Library and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Bellows also illustrated numerous books in his later career, including several by H.G. Wells.

Bellows taught at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1919. In 1920, he began to spend nearly half of each year in Woodstock, New York, where he built a home for his family. He died on January 8, 1925, in New York City, of peritonitis, after failing to tend to a ruptured appendix. He was survived by his wife, Emma Story Bellows (married 1910), and daughters Anne and Jean. Bellows is buried at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. "Of American artists of the first rank," wrote Joyce Carol Oates, "none had a more tragically foreshortened career than Bellows.... [He was] the most famous American artist of his time."

Paintings and prints by George Bellows are in the collections of many major and regional American art museums, including the Art Museum of Southeast Texas in Beaumont, Texas, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, Rochester, New York, and the Whitney and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and The Hyde Collection, in Glens Falls, New York. The Columbus Museum of Art in Bellows' hometown also has a sizeable collection of both his portraits and New York street scenes. The White House acquired his 1919 painting Three Children in 2007, and it is now displayed in the Green Room.

The Whitney Museum of American Art published a biography of Bellows by fellow artist George William Eggers as part of the American Artists Series. In 1992 it mounted an extensive exhibition of his art (the exhibition was a joint venture with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art).

The Archives and Special Collections at Amherst College holds his papers.

Posthumous sales and exhibitions

His work was part of the painting event in the art competition at the 1932 Summer Olympics.

In December 1999, Polo Crowd, a 1910 painting, sold for U.S.$27.5 million to billionaire Bill Gates. In November 2008, Bellows' Men of the Docks, a 1912 painting of the Brooklyn docks spanning the East River and depicting the Manhattan skyline in the background, was to be auctioned at Christie's in New York. It was expected to set the record for an American painting sold at auction with an estimate of $25–35 million. The painting's sale however was a source of controversy at Randolph College because it was the first masterpiece purchased for the Maier Museum of Art by students and locals who raised $2,500 to purchase it in 1920.Due to a series of lawsuits and the deflated art market, the painting remained unsold until 2014 when it became the first major American painting to be purchased by the British National Gallery in London.

In 2001, Thomas French Fine Art became the exclusive agent of the George Bellows Family Trust.

Randolph College was asked by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., to lend Men of the Docks, for inclusion in a 2012 exhibition. A major Bellows retrospective was held at the Royal Academy in London in 2013. Men of the Docks is now in the National Gallery in London. In November 2021, the Columbus Museum of Art opened the George Bellows Center to encourage exhibitions, publications and scholarly research on his life and work. Noted Bellows scholar Mark Cole of the Cleveland Museum of Art presented a lecture on Bellows' life with a specific focus on sports subjects in his work.

|

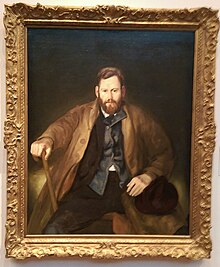

| Self-Portrait, 1921 George Bellows |

George Bellows (1882–1925) was regarded as one of America's greatest artists when he died, at the age of forty-two, from a ruptured appendix. Bellows's early fame rested on his powerful depictions of boxing matches and gritty scenes of New York City's tenement life, but he also painted cityscapes, seascapes, war scenes, and portraits, and made illustrations and lithographs that addressed many of the social, political, and cultural issues of the day. Featuring some one hundred works from Bellows's extensive oeuvre, this landmark loan exhibition is the first comprehensive survey of the artist's career in nearly half a century. It invites the viewer to experience the dynamic and challenging decades of the early twentieth century through the eyes of a brilliant observer.

Born and raised in Columbus, Ohio, Bellows attended Ohio State University, where his athletic talents presaged a future in professional sports and his illustrations for the student yearbook heralded a career as an artist. In 1904, he left college and moved to New York to study with Robert Henri, under whose influence he became the leading young member of the Ashcan School. The Ashcan artists aimed to chronicle the realities of daily life, but often depicted them through rose-colored glasses. Bellows, the boldest and most versatile among them in his choice of subjects, palettes, and techniques—and also the youngest—treated both the immigrant poor and society's wealthiest with equanimity.

Bellows never traveled abroad but learned from the European masters by seeking out their works in museums, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he was a regular visitor. In 1911, the Museum acquired one of his Hudson River scenes, Up the Hudson, making him one of the youngest artists in the collection at that time; he was twenty-nine years old. Over the years, ten more paintings, six drawings, and some fifty prints were added to the Met's holdings.

Although Bellows's art was rooted in realism, the variety of his subjects and his experiments with many color and compositional theories, and his loose brushwork, aligned him with modernism—as did his commitment to artists' freedom of expression and their right to exhibit their works without interference from academic dictates or juries.

When Bellows died in January 1925 at age forty-two, his career was still a work in progress. Acknowledging his important role in American art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art organized the artist's first museum retrospective in 1925 as a memorial exhibition.

By the fall of 1904, Bellows had arrived in New York City, intent on pursuing a career as an artist. He boarded at the YMCA on Fifty-seventh Street and enrolled at the nearby New York School of Art, where he quickly fell under the influence of his teacher Robert Henri (1865–1929). Henri urged his students to move beyond the genteel scenes then favored by the conservative members of the National Academy of Design and the American Impressionists to seek out contemporary subjects that might challenge prevailing standards of taste. Responding to Henri's teachings, Bellows focused on the city's impoverished immigrant population. In their originality, thematic range, and varied technique, his early works soon surpassed the efforts of his talented classmates Edward Hopper (1882–1967) and Rockwell Kent (1882–1971). Bellows paid particular attention to the children who inhabited the squalid and dangerous slums. In complex multifigured compositions brimming with vitality, he captured his subjects' lives on the precarious margins of society.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Forty-two Kids, 1907. Oil on canvas. 42 x 60 in. (106.7 x 152.4 cm). Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Museum Purchase, William A. Clark Fund

Forty-two Kids, painted in August 1907, depicts a band of boys sunning themselves and bathing in Manhattan's muddy East River. In turn-of-the-century slang, "kids" referred to the streetwise children of recently arrived, working-class immigrants living in Lower East Side tenements. The canvas was initially awarded the Lippincott Prize at the 1908 annual exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, but the honor was withdrawn over fears that the sponsor would object to the naked children. Bellows commented, "No, it was the naked painting they feared." Nonetheless, Forty-two Kids was purchased within a year of its completion, marking the second sale of Bellows's career.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Beach at Coney Island, 1908. Oil on canvas, 42 x 60 in. (106.7 x 152.4 cm). Private collection

Having painted tenement kids enjoying themselves along the banks of Manhattan's East River, Bellows turned for a subject to Brooklyn's Coney Island, a popular beach destination for diverse crowds seeking relief from the summer heat. Relaxed moral codes had long been associated with the resort, although the construction of new amusement parks and other attractions promised reforms. Bellows signals promiscuousness with the amorous man and woman at lower left, who capture the attention of several other figures. One leading critic described Bellows's crowded composition as "a distinctly vulgar scene."

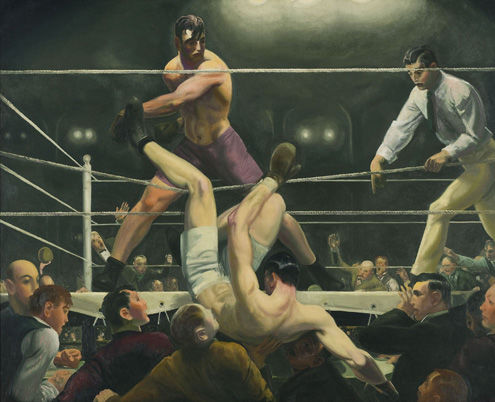

Having played basketball and baseball in college, Bellows was attracted to all kinds of sports and used them as subjects throughout his career. His early fight scenes, made over a period of little more than two years, capture the passion for boxing that prevailed about 1900, reflected also in Jack London's writings and in Theodore Roosevelt's engagement with the sport as an amateur fighter. Bellows recorded brawls at the sleazy athletic club run by the retired pugilist Tom Sharkey, located opposite his studio at Broadway and Sixty-sixth Street. Clubs such as Sharkey's evaded a 1900 ordinance outlawing public prizefighting by selling memberships—to men only—instead of charging admission. Seizing the essence of raw male aggression in his boxing pictures, inscribing their intensity in slashing brushwork, Bellows repudiated Victorian piety and provoked critical controversy. Exploring the fundamental theme of human violence through one of the most provocative subjects of his day, he created works that were at once timeless and topical. During this period Bellows also painted portraits of the city's working poor, conveying his sitters' vulnerability as well as their resilience. These frank encounters reveal Bellows's grasp of the realist portrait tradition practiced by Édouard Manet, Frans Hals, and Diego Velázquez and his circle, all of whom his teacher Robert Henri had commended to him, and whose works he studied at the Metropolitan Museum.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Stag at Sharkey's, 1909. Oil on canvas, 36 1/4 x 48 1/4 in. (92.1 x 122.6 cm). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Hinman B. Hurlbut Collection, 1133.1922

The savage energy of Stag at Sharkey's is concentrated in the two brutal boxers. Many of the grotesque patrons at ringside are flushed and thrilled to be cheering on the vicious bout. As Bellows observed in a 1910 letter to an Ohio acquaintance, "the atmosphere around the fighters is a lot more immoral than the fighters themselves." Crouched in the first row at the far side of the ring, under the referee's outstretched arm, is a figure who seems to be peering up from his sketch pad, perhaps a stand-in for Bellows himself.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Paddy Flannigan, 1908. Oil on canvas, 30 1/4 x 25 in. (76.8 x 63.5 cm). Erving and Joyce Wolf

Arriving in New York in 1904, Bellows must have been fascinated by the diversity of faces he encountered, especially in the immigrant neighborhoods of the Lower East Side—Italians, Irish, and European Jews. Like his teacher Robert Henri, Bellows painted a number of formal portraits of the children who hung out on the streets or who were forced to work as laundresses, newsboys, and street laborers at a young age before labor laws were enacted. Dramatically posed against a dark background like one of the Old Master paintings by Rembrandt, Hals, and Caravaggio that he studied at the Metropolitan Museum, Bellows captures Paddy Flannigan’s sense of impudence and survival. One art critic described him as a "pearl of the gutter."

Bellows, who had been raised in Columbus, Ohio (population 125,000 in 1900) explored New York (population 3.5 million in 1900) with wonder and curiosity. Among his early paintings depicting the city is a series of canvases recording the excavations for the Pennsylvania Railroad Station. Bellows also painted Manhattan's river-bound borders, only rarely portraying its bustling commercial or theater districts. Beginning in 1908, he devoted several canvases to Riverside Park on Manhattan's Upper West Side, which had been designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in 1873 and was just nearing completion. Some of Bellows's scenes look across the Hudson River to the Palisades, steep cliffs along the west side of the river that were then the focus of conservation efforts. Although Bellows envisaged Riverside Park as an urban oasis, he acknowledged such modern intrusions as steamships on the Hudson and trains running along its shore.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Pennsylvania Excavation, 1907. Oil on canvas, 33 7/8 x 44 in. (86 x 111.8 cm). Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts. Gift of Mary Gordon Roberts, class of 1960, in honor of her 50th reunion

One of the largest building projects in the country, Pennsylvania Station entailed the razing of two city blocks—from Thirty-first to Thirty-third Streets between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Completed in 1910 (and demolished 1963–66), it covered eight acres and featured a magnificent terminal designed in the Beaux-Arts style by the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White. Bellows, however, was much less interested in the splendid structure than in the primordial pit where workmen toiled and sometimes lost their lives.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Rain on the River, 1908. Oil on canvas, 32 x 38 in. (81.3 x 96.5 cm). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Jesse Metcalf Fund

Like Frederick Law Olmsted's other landscape designs, Riverside Park was an object of civic pride. Bellows's view of the park and the Hudson River, as seen from adjacent Riverside Drive, celebrates commercial and industrial elements, as well as impressive natural features. It suggests the press of the city toward its boundaries and the uneasy truce between urban development and much-needed recreational spaces.

Bellows once commented that "there is nothing I do not want to know that has to do with life or art." He drew equal inspiration from municipal workers removing snow from the city's streets, longshoremen loading and unloading cargo from ocean liners and freighters, and the ladies and gentlemen who created a rich visual pageantry as they enjoyed New York's parks. The variety of Bellows's urban subjects was matched by the range of palettes and techniques he employed, often on immense canvases. Few would have disputed a critic who observed of Bellows at the time of his death, "He was an adherent of 'wallop' in painting." In an astute bid for broad appeal, Bellows exhibited his works widely, attracting both critics—"There's been an awful lot written about me," he admitted—and patrons. His dramatic paintings of familiar subjects were acquired by major museums, important regional art centers, educational institutions, and prominent collectors, from the relatively adventurous to those with more conventional tastes. Both an active academician and a keen independent, Bellows was at home among diverse factions of the art world. Writing in 1913, the critic Forbes Watson noted his "curious appeal" to "the conservative and radical alike."

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Blue Snow, The Battery, 1910. Oil on canvas, 34 x 44 in. (86.4 x 111.8 cm). Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio: Museum Purchase, Howald Fund

Bellows depicts Battery Park, at the southern tip of Manhattan, under a blanket of fresh snow. Tugboats are barely visible in the distant harbor’s dark blue water. Bellows suggests a nearly rural quality, even in an urban setting, emphasizing smooth, flat expanses of space and a sense of emptiness, despite the presence of a few quickly painted pedestrians. This was one of eighteen oils that Bellows included in his first solo exhibition, in January 1911. Although one critic mocked its aggressive paint handling as "assault and battery," most others praised Bellows's technique. One wrote, "He suggests life and force by the swiftness of his brush stroke and the elimination of non-essential forms."

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). New York, 1911. Oil on canvas, 42 x 60 in. (106.7 x 152.4 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1986.72.1

Bellows generally preferred to paint Manhattan's periphery. In this unusual composite view of a midtown business district, which pertains most closely to Madison Square, he presents the city as a place in constant flux. Packing the scene with skyscrapers, billboards, and chimneys spewing smoke; an elevated train station and tracks; horse-drawn carriages and motorcars snarled in traffic; and sidewalks filled with men and women of all economic backgrounds, he denies the viewer's eye a resting place. New York's modern tumult, with countless details of sight and sound crowding in on one another, was as new and impenetrable to Bellows as it was to any of his contemporaries.

In August 1911, at the invitation of his teacher Robert Henri, Bellows made the first of five visits to Maine, long a popular destination for artists. There, he captured the awe-inspiring natural forces that shaped the region, and portrayed the fishermen who made their living from the surrounding waters. Bellows was especially drawn to Monhegan Island, a rocky landmass barely a mile square, located ten miles off the midcoast. Winslow Homer's Maine seascapes of the 1890s—four of which were in the Metropolitan Museum's collection by 1911—inspired Bellows, but he exceeded even Homer in distilling nature to its fundamental elements. Bellows usually painted outdoors, on small panels that he could develop into large canvases in his island studio or when he returned to New York City. While nature was his primary focus, he did produce a series of paintings on his final visit in 1916 that featured shipbuilders at work in Camden, Maine. In northern California the following summer, Bellows once again found inspiration in the sea. The more than 250 seascapes and shore scenes that he created between 1911 and 1917 account for half of his output as a painter.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Churn and Break, 1913. Oil on panel. Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio, Gift of Mrs. Edward Powell

Some of Bellows's most powerful paintings from 1913 are close-up views of surf crashing against the rocky shore. Disorienting in their compressed space and obscured horizons, they recall Winslow Homer's late seascapes, such as Northeaster (1895, The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Like Homer, Bellows used exuberant brushstrokes and viscous oil paint to convey the swelling motion and explosive sprays of water and foam, but he went beyond Homer's example to suggest nature's unbridled energy. Painting directly on a panel, as here, or on canvas, without making preliminary sketches, he applied his colors wet-into-wet, rather than mixing them on a palette. He may have been inspired to use such modern methods after seeing avant-garde art at New York's Armory Show earlier that year.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). The Big Dory, 1913. Oil on panel, 18 x 22 in. (45.7 x 55.9 cm). New Britain Museum of American Art, Harriet Russell Stanley Fund

The year 1913 was particularly eventful for Bellows. He exhibited six oils and eight drawings in New York's Armory Show of international modern art (from February to March), and that spring he became a full member of the National Academy of Design. From July to October, he threw himself into work on Monhegan and Matinicus Islands, Maine, in the company of his family and the artist Leon Kroll, a noted colorist. There, he created more than one hundred small panels (each about fifteen by twenty inches) and thirteen slightly larger, more ambitious compositions such as The Big Dory. These pictures featured more color than Bellows had used before, and emphasized the relationship between man and nature.

Bellows was always a gifted draftsman. After he installed a printing press in 1916 in his home studio on East 19th Street in Manhattan, he also mastered lithography, a printmaking technique that depends directly on drawing. Between 1916 and his death in 1925, he produced about two hundred editions, totaling eight thousand impressions. Lithography became an integral part of his creative process as he developed subjects across different media, moving easily between drawings, paintings, and prints—not always in that order. Issued in editions of twenty-five, fifty, or one hundred, his prints were affordable and kept his most popular images in the public eye. Although they sometimes repeated subjects of earlier date, they were never exact copies of those works; rather, they reflected his rethinking of specific details, tonal values, size, and scale to alter the visual effect.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Cliff Dwellers, 1913. Oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 41 1/2 in. (100.3 x 105.4 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Fund

The term "cliff dwellers" refers to the Native Americans of the Southwest who lived in stratified cave dwellings cut into the sides of steep cliffs. Here, multistory tenement buildings on the Lower East Side are overcrowded to the point of bursting. Residents spill onto the streets and hang out of windows to get some relief from the summer heat. Penned in by walls of brick, they seem unable to escape their circumstances. As one New York City official lamented, "It is simply impossible to pack human beings into these hives . . . and not have them suffer in health and morals." While the picture appears to have a political agenda, Bellows professed his commitment only to personal and artistic freedom.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Drawing for "The Cliff Dwellers", 1913. Transfer drawing, reworked with lithographic crayon, ink, and scraping, 22 x 19 in. (55.9 x 48.3 cm). Private Collection

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Why Don't They Go to the Country for Vacation?, 1913. Transfer drawing, reworked with lithographic crayon, ink, and scraping, 25 x 22 1/2 in. (63.5 x 57.2 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Fund

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). The Cliff Dwellers, 1913. Watercolor and pen and brush and black ink on wove paper, 21 1/4 x 27 in. (54 x 68.6 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Olivia Shaler Swan Memorial Collection

These drawings for Bellows's oil painting Cliff Dwellers illustrate how the artist spent a fair amount of time thinking about the narrative details and compositional arrangements of his large oil paintings. In the two black-and-white transfer drawings, he changes some small elements within the same overall composition: for example, including a woman on the fire escape hanging laundry in the upper right corner of Drawing for "Cliff Dwellers" (private collection), and filling in the space in front of the streetcar at the left center edge in Why Don't They Go to the Country for Vacation? (Los Angeles County Museum of Art). His differing distribution of light and dark areas in these two drawings serves to highlight different vignettes. The third drawing, The Cliff Dwellers (Art Institute of Chicago), is a much more detailed, close-up view, in color, of the young girl scolding a crying boy at the bottom of the painting.

The reported atrocities committed by German soldiers against Belgian civilians during World War I prompted Bellows to undertake his most ambitious, and ultimately most problematic, cycle of works. Devoting himself to the project between the spring and fall of 1918, he created many drawings, lithographs, and five monumental oil paintings (four of which are on view in the exhibition) that imagine in horrific detail the acts described in the American press and in the British government's Bryce Committee Report (1915). It was one of the few times that Bellows had not observed his subjects firsthand. Although Bellows initially was ambivalent about America's entry into the war, in April 1917, and did not serve in the military, his pictures were used for propaganda and to sell war bonds. Bellows's adherence to the artist Jay Hambidge's theory of "Dynamic Symmetry" gave these compositions the appearance of tableaux, with figures frozen on well-lit stages. The artificiality of their structure played against the graphic violence depicted, making them visually arresting but deeply disturbing. Throughout 1919 they were widely published and exhibited, but after the accuracy of the Bryce Committee Report was called into question, the most explicitly violent images were rarely, if ever, shown.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Massacre at Dinant, 1918. Oil on canvas, 49 1/2 x 83 in. (125.7 x 210.8 cm). Greenville County Museum of Art, South Carolina, Gift of Minor M. Shaw, Buck A. Mickel, and Charles C.Mickel; and the Arthur and Holly Magill Fund

In July 1918, Bellows completed this painting, the first of five in his war series. It memorializes the slaughter of 674 Belgian citizens, including women and children, in the town of Dinant on August 23, 1914, shortly after war had begun. The dead lie in the foreground, while a mass of helpless clergy and townspeople behind them avert their eyes from their own likely fate. At the far left, as dark storm clouds roll in, the arrival of more German troops is signaled by the bloodied bayonet held by a partially visible soldier and the barrage of raised rifles.

Aside from his early portraits of street urchins in New York, and a few commissioned portraits, most of Bellows's human subjects feature his family and acquaintances. They include his parents and fellow artists, family friends and neighbors, and most important, his wife Emma (whom he married in 1910) and their daughters Anne and Jean. Although he is better known for his sporting scenes and pictures of New York City, his portraits were exhibited frequently and won a number of prizes. His depictions of women portray them at all stages of life and offer a compelling counterpoint to the essentially male world of his boxing paintings.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Emma at the Piano, 1914. Oil on panel, 28 3/4 x 37 in. (73 x 94 cm). Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr

Bellows's wife, Emma, was his lifelong artistic muse. They met as fellow students at the New York School of Art, shortly after Bellows arrived in the city, and were married in 1910. Bellows painted Emma in many guises, at times evoking the creative dimensions of their shared life. For example, Emma at the Piano unites visual and musical elements in ways that recall James McNeill Whistler's subtly orchestrated portraits, also painted with limited palettes. Expressing how central Emma was to his artistic identity, Bellows wrote to her early in their marriage, "Can I tell you that your heart is in me and your portrait is in all my work? What can a man say to a woman who absorbs his whole life?"

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Mrs. T in Cream Silk, No. 1, 1919. Oil on canvas, 48 x 38 in. (121.9 x 96.5 cm). Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, The Joseph H. Hirshhorn Bequest, 1981

Bellows painted two compelling portraits of Mrs. Mary Brown Tyler, a socialite in her late seventies whom he met in the fall of 1919 while he was teaching at the Art Institute of Chicago. Known for her old-fashioned attire and wit, Mrs. Tyler first posed for him in a lavish wine-colored silk dress, which heightened her complexion. At his request, she posed again (here) in her 1863 cream silk wedding gown, which emphasized her pallor. Both canvases call to mind portraits by Thomas Eakins, whose probing realism Bellows had inherited through Robert Henri and had seen firsthand in the 1917 memorial exhibition of Eakins's works at the Metropolitan Museum.

During what were to be his last years of life, Bellows spent the summers in Woodstock, New York, a rural arts community in the Catskill Mountains. There, he communed with nature, the local townspeople, and a close circle of family and artist-friends, including Leon Kroll, Charles Rosen, and Eugene Speicher. Other artists such as Andrew Dasburg, Henry McFee, and Konrad Cramer were also part of his social circle, although he did not follow their modernist approach. Bellows made small bucolic landscapes in Woodstock, but his most important works from the period were the monumental figure paintings he executed with Old Master grandeur. Many of these were also painted in Woodstock, while others were begun there and finished in New York City. Traditional in subject and regimented in structure, they often referenced well-known paintings that he knew from the Metropolitan Museum's collection or had seen in reproductions. Bellows's last masterpiece, Dempsey and Firpo (1924; Whitney Museum of American Art), embodies the era's Machine Age aesthetic and Art Deco sleekness. The questions it raises about a new direction for his art were, however, never answered. On January 8, 1925, at the age of forty-two, Bellows died from a ruptured appendix. The writer Sherwood Anderson concluded that Bellows's last paintings "keep telling you things. They are telling you that Mr. George Bellows died too young. They are telling you that he was after something, that he was always after it."

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Emma and Her Children, 1923. Oil on canvas, 59 1/4 x 65 3/8 in. (150.5 x 166.1 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Subscribers and by purchase from the John Lowell Gardner Fund

Just weeks after his mother died, Bellows painted his wife and children seated on her Victorian loveseat. It is the first of six different portraits of various people that incorporates this piece of furniture. This painting is often compared to Auguste Renoir's Madame Georges Charpentier and Her Children Georgette and Paul (1878), which Bellows had seen at the Metropolitan Museum, but its somber palette and stoic poses seem closer to the Old Master paintings, which he also admired at the Met, than to Renoir's Impressionism.

George Bellows (American, Columbus, Ohio 1882–1925 New York City). Dempsey and Firpo, 1924. Oil on canvas, 51 x 63 1/4 in. (129.5 x 160.7 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney

In one of his last paintings, Bellows returned to the subject of boxing, which had established his reputation. Having been commissioned to depict the Dempsey v. Firpo championship fight on September 14, 1923, at New York's Polo Grounds, he immortalized the most startling moment of the first round in a stop-action freeze frame. The Argentinian challenger, Luis Ángel Firpo, has knocked the champion, Jack Dempsey, out of the ring—although Dempsey would go on to triumph in the second round. The stylized figures, limited palette, and dramatic tension capture the essence of the sport and seem to signal a new—and unrealized—direction for Bellows's art.

.jpg)